Bud Krogh, John Ehrlichman's deputy, served a little time, such was his commitment to Nixon.

Fred LaRue was an adviser to John Mitchell, raised hush money for the burglars, and was suspected of endorsing Mitchell's approval of the Watergate break-ins.

Herbert Porter was the assistant to Jeb Stuart Magruder. He was also a USC Mafia graduate, something he shared with Press Secretary Ron Zeigler, Dwight Chapin, Gordon Strachan and Donald Segretti. Porter moved into the Nixon camp as a result of the arrangements he made for the Tricky One's 1968 Phoenix speech (the one where Nixon referred to anti-war demonstrators as "violent thugs"). Clean-cut weasel rat who developed a conscience when it was obvious that he would be fond guilty.

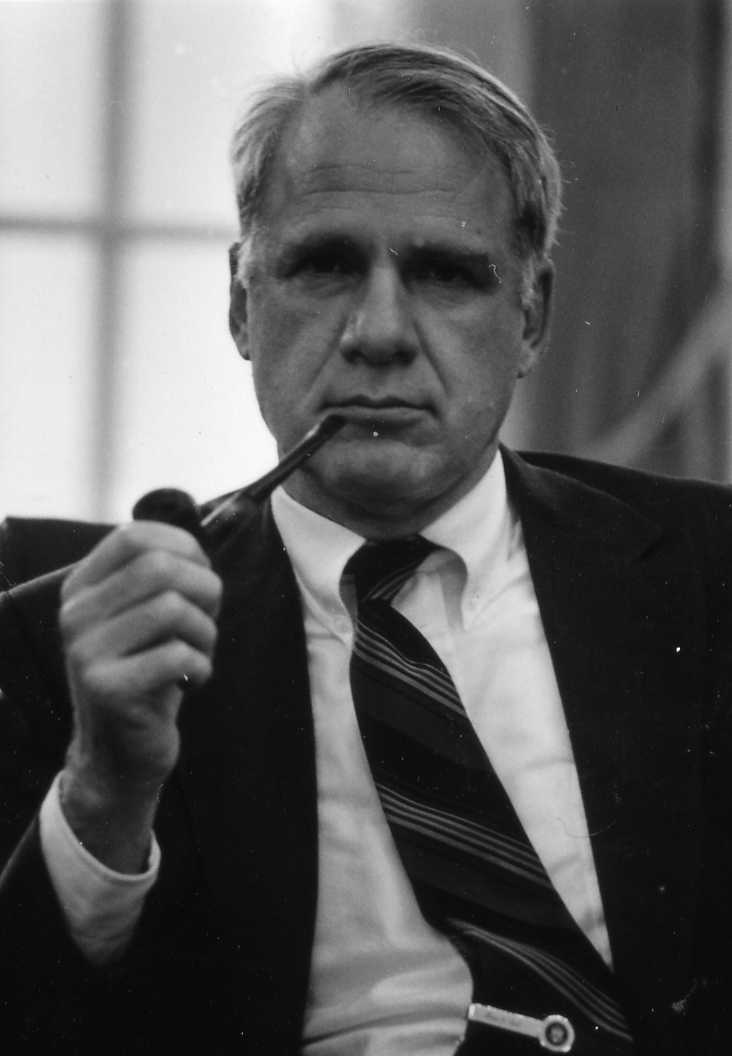

Donald Segretti served as a freelance saboteur for the Nixon campaign. USC typhoid case who completed the true believer mold by moving from the far left to the far right because it seemed politically expedient.

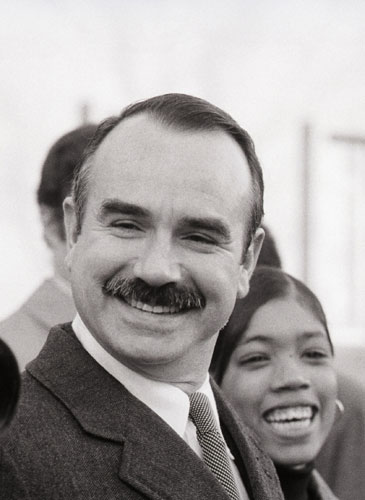

Maurice Stans was Nixon's Secretary of Commerce. He plead guilty to five charges of campaign finance law violations (three involving his record keepings and two involving illegal contributions from Robert Vesco).

Tony Ulasewicz was the White House private detective. He received illegal income from Herbert Kalmbach and was found guilty of filing fraudulent income tax returns for two consecutive years.

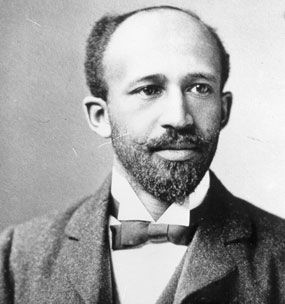

E. Howard Hunt was far and away the most interesting of all the Watergate convicts. Hunt's history deserves some elaboration. Born October 9, 1918, in Hamburg, New York, he graduated from Brown University in 1940, Phi Beta Kappa, with a degree in English Literature. He thereafter enlisted in the National Officers Training Program. Hunt was injured during World War II and soon became a correspondent for Life magazine. He later joined the Army Air Force and through connections there, worked for the Officers Strategic Services where he performed sabotage against the Japanese. After a brief and unsatisfying stint in the motion picture industry, Hunt became the press aide to the European Director of the Marshall Plan. By 1948 his anti-communist paranoia had brought him to the happy attention of the CIA. He claims to have worked for them from 1949 until 1970. During this period he was quite active, in 1950 serving as Chief of Station in Mexico City and in 1954 participating in the violent overthrow of the Arbenz government, a coup d'etat that permitted a dictatorship to seize control of Guatemala. Spring-boarding from his success in one Latin American country, he served with the anti-Castro exiles in Brigade 2506's failed attempt to overthrow the Cuban government. For the remainder of his life, Hunt continued to blame the failures of the mission on what he disingenuously and mistakenly perceived as John Kennedy's refusal to provide air support.

Such counterrevolutionary activities are preamble to testimony by Maria Lorenz, a woman who performed work for both the CIA and the FBI. According to her testimony in Hunt v. Liberty Lobby, the day before JFK's assassination, she witnessed Hunt--whom she knew as Eduardo--paying future Watergate burglar Frank Sturgis a sum of money in Dallas, a sum intended to finance the murder and facilitate the escape. Lorenz testified that Sturgis admitted his participation as well as that of Hunt as paymaster. The witness did not dissemble on cross-examination and Hunt ultimately lost his defamation suit against the far right Liberty Lobby.

In case the reader is unfamiliar with the man whose working alias ran the narrow gamut between Eduardo and Ed Warren, here is a list of deeds for which Mr. Hunt has been credited:

- Recruiter and organizer in the overthrow of the democratically-elected government of Guatemala;

- Participant-coordinator of the failed invasion of Cuba at the Bay of Pigs;

- Paymaster in a domestic assassination;

- Employee of the CIA while pretending to do public relations for an Agency front, the Robert J. Mullen Company;

- Author of a forged cable stating that President John Kennedy had authorized the murder of South Vietnamese President Diem;

- White House employee empowered to gather intelligence on Senator Ted Kennedy's involvement in the Chappaquidick affair;

- Co-conspirator in the burglary of the office of Daniel Ellsberg's psychiatrist;

- Co-conspirator with Gordon Liddy in plot to murder columnist Jack Anderson;

- Asset in plan to firebomb the Brookings institute;

- Inducer to commit perjury in the Dita Beard-ITT scandal;

- Would-be pimp in attempt to enlist prostitutes to seduce secrets from opponents at political conventions;

- Conspirator in the Watergate burglaries;

- Blackmailer to the President of the United States;

- Suspected author of pro-McGovern literature found in apartment of would-be assassin Arthur Bremer.

This list is no doubt incomplete. As of this writing, Mr. Hunt remains dead and has therefore paid for the crimes for which his guilt has been determined. Child molesters freed after serving proscribed sentences have done the same. The advantage Hunt maintained over monolithic industrialists and sex offenders is that he convinced many people--including himself--that his behavior was all for the greater good. For instance, Hunt maintained that his various nefarious attempts to disrupt american political elections only served to reveal the true nature of the opposition party, thereby allowing the American people to make an informed choice. Of course, this defense ignores a crucial distinction. Hunt's methods for providing revelations about political opponents were, first, covert to avoid interference in execution, hidden after the fact to avoid prosecution, and finally subject to plausible deniability to avoid conviction.

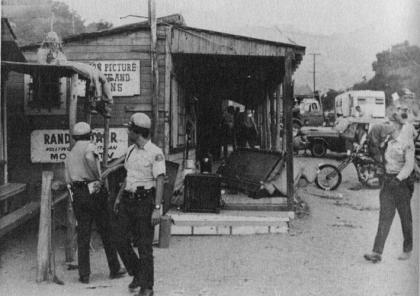

Hunt's activities from the time of the Kennedy assassination through 1970 have been muted. But his operations after joining the Nixon White House are well documented. One such operation was a campaign against Daniel Ellsberg and his attorney Lawrence Boudin. The operation involved performing a covert psychological evaluation of Ellsberg, ghostwriting news articles about him, and burglarizing the offices of his psychiatrist, Dr. Lewis Fielding. When the compulsive spy wasn't discrediting private citizens, he was falsifying State Department cables to show that Kennedy has ordered the assassination of South Vietnamese President Diem and showed the forgeries to Bill Lambert of Time-Life, purporting them to be valid. According to Gordon Liddy, around this same time, as part of Operation Gemstone, he and Hunt propagated allegations against the wife of candidate Ed Muskie, forged a letter from Muskie referring to Canadians as "canucks" and planned the firebombing of the Brookings Institute.

In a marvelous interview with David Giammarco in 1999, Hunt remained unrepentant. "You know, I once heard from a fellow who worked for me, a retired colonel, who said 'There's a feeling around here that you let the Agency down, and that you're responsible for the disfavor in which the Agency is held by the general public.' If anything, the Agency owes me an apology because they were the ones who revealed my covert connection, after thirty years of building up a cover."

Regarding his involvement in the original By of Pigs fiasco, Hunt admits, "I went to Cuba a couple months before and talked to people in all walks of life. And I concluded that any invasion force could not expect any assistance from the Cuban people."

"History will be a lot less kind to me than it's been to Richard Nixon," Hunt concludes. "My caption will read: Watergate burglar dies at 80-plus. He was implicated in the Kennedy assassination."

As Nixon supporters hasten to point out, Milhous did win his second term, capturing 60.7 percent of the popular vote. A combination of dirty tricks and happenstance made this inevitable as Muskie fell apart emotionally in New Hampshire when the Gemstone People verbally assaulted his wife, when Henry Jackson was shown to be more reactionary than Nixon himself, when George Wallace was shot and crippled, when Shirley Chisholm was revealed to be an African American woman, and when George McGovern was discredited by his own people.

In the 1960 Presidential debates between Richard Nixon and John Kennedy, then Vice President Nixon attacked his opponent for repeatedly "running down America." Although Kennedy finally replied that he did not need a civics lesson from the likes of Nixon and went on to explain that he had not criticized America but had rather questioned the behavior of certain people in it, still Nixon never quite dropped the patriotism issue that had served him so well in the past. It would be the same Nixon who accused anti-war protesters in the United States of prolonging the Vietnam War by showing communists that Nixon did not have the support of all Americans. Of all the positions available to the President on the peace movement, this was the most cowardly and despicable. A braver and nobler man might have admitted his own inability to have everyone agree with him. But Nixon preferred smearing and shooting to rational thought, as the mothers of four murdered Kent State students could attest. Presumably Nixon meant that citizens in a democracy should voluntarily inhibit their First Amendment rights in order to make it easier for the White House to wage war on its own terms. Any criticism of public policy was interpreted as an attack on the USA.

Even someone as psychotically paranoid as Nixon tried to not overreact all of the time. And initially he and his aides consoled each other that the Watergate operation's real magnitude would not be revealed. After all, the media was not terribly interested in pursuing the story. With the exception of The Washington Post, very little was reported in the national news until burglar James McCord finally decided the White House was going to let the court fail to investigate and so he began sending letters to Judge John Sirica. Learning of this, the print media could no longer ignore the story, particularly once it was announced that McCord would be appearing before Senator San Ervin's Select Committee.

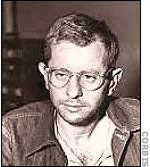

Frank Fiorini, also known as Frank Sturgis, Watergate burglar, Brigade 2506 coordinator, was also a reputed Kennedy assassination conspirator, at least according to testimony given by Marita Lorenz.

Bernard Barker was an associate of Howard Hunt. He told Ervin's Select Committee that he had been involved in a plan to physically harm Daniel Ellsberg while the latter was speaking at an anti-war demonstration. Barker was a Watergate burglar and Bay of Pigs refugee who identified himself at his burglary arraignment as an "anti-communist," an occupation he shared with burglars Virgilio Gonzalez, Eugenio Martinez, Alfred Baldwin, and James McCord.

When asked his occupation by the arraignment judge, McCord stated with apparent unease that he worked for the CIA. Supporting that admission is the fact that once Howard Hunt learned of the burglars' arrest, he contacted an attorney named Douglas Caddy, a man who had worked for the ultra conservative Young Americans for Freedom and also as a legal contract agent for Central Intelligence. Caddy represented the five burglars.

The involvement of at least two CIA operatives (McCord and Hunt) in an operation that was botched in one of the stupidest ways imaginable--the door bolt was taped to stay open, but instead of securing the tape vertically so it would not be detected by passing security guards, it was placed horizontally, not once but twice, so that there could be no doubt that it would be detected--leads the more suspicious thinkers to wonder if perhaps with Gordon Liddy's Gemstone there may have been a sub-operation to dismantle Nixon. There is not a wealth of evidence to support this conjecture and conjuring a motive for such CIA actions is a stretch; yet given the tenacity of CIA experts Bob Woodward and Jack Anderson, it does make for interesting speculation.

Initially Nixon had made overtures to bond with the CIA. The most pronounced of these was his installment of Marine Corps General Robert Cushman as Deputy Director of Central Intelligence, a move that was largely ineffective due to Director Richard Helms correctly perceiving that Cushman was a spy for Nixon. Nor were White House relations with the Agency helped when Stuart Symington, the Democratic Senator from Missouri, attacked the "cloak of secrecy" that his U.S. involvement in Laos. In October 1969, The New York Times ran several articles about the "secret war in Laos," those articles detailing that the Green Berets had led Meo operations while on contract to the CIA. The ensuing controversy was all the provocation Nixon needed. He ordered the Agency to demonstrate that involvement in Laos had begun under the presidency of his predecessors.

Seeing covert actions as a useful tool of administration policy, Nixon proved to be much more involved in controlling the CIA than were any presidents before him. In February 1970, the President's National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger drafted National Security Decision Memorandum 40, establishing the Forty Committee to oversee Agency black operations. Committee Forty members were the Deputy Secretaries of State and Defense, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs, Director of Central Intelligence, and Kissinger himself as Chair. Not every CIA operation came under the scrutiny of the Committee. It only affected the 99 percent that cost more than $25,000, that supported political or military groups, those of an economic, paramilitary or counterinsurgency nature, or those that were politically sensitive.

Even critics of Nixon could admit the CIA needed controlling. At the time of Committee Forty's formation, Nixon ordered the destruction of "all existing toxic weapons." The CIA ignored this directive. One month later, Cambodian head of state Prince Norodom Sihanouk was ousted by a violent coup d'etat backed by the CIA, an action that installed Marshall Lon Nol in the prince's place. This in turn made Nixon's April 1970 bombing of Cambodia arguably retaliation for a CIA action.

Meanwhile, Operation Chaos expanded. White House aide Tom Houston let it be known that the President would be happy if the program were to encompass domestic groups, especially political opponents and members of the anti-war movement. Thus began the Huston Plan, which involved the CIA in a domestic mail-opening operation and which arranged for evaluation of data on dissent groups collected by the FBI, CIA, NSA and DIA.

Nixon and the CIA likewise had mutualities of interest in negating the democratically-elected Socialist Salvador Allende in Chile. Concerned over anticipated nationalization of industries involving ITT, Nixon authorized Central Intelligence Director Richard Helms to spend up to ten million dollars and to use his best agents to stop Allende at all costs.

Allende was stopped. Nazi General Pinochet was installed. Terror reigned.

A final issue that bonded the Nixon White House with the CIA was the former's protection of the latter. In the early spring of 1972, Central Intelligence Director Richard Helms learned that a former operative, Victor Marchetti, had written a book about his own time in the Agency. The Director appealed to Nixon for help in quashing any damaging material The CIA and the Cult of Intelligence might contain. Helms argued that the expose would damage national security. Such "tell all" books were more rare in the early 1970s than today and so the Nixon administration took civil action to block the book's release. The actions delayed publication for better than two years. The suit argued that as an employee of the CIA, Marchetti had signed a secrecy agreement which forbade him from divulging security secrets. When the book was finally published in 1974, it was without 168 deletions demanded by the CIA. Not missing from the manuscript was the author's thesis that the Agency had become dangerous due to a "cult of intelligence" determined by the Helms' "mystique of secrecy." Loyalty to the CIA, such as it was, apparently did not extend to the Dire tor. After winning re-election in November 1972, Nixon fired Helms.

Four conversations that took place prior to Watergate:

Haldeman: Huston swears to God there's a file at Brookings.

Nixon: I want it implemented. Get in there and get those files. Blow the safe and get it.

--June 17, 1971

Ehrlichman: Now I'm going to steal those documents out of the National Archives.

Nixon: You can do that, you know.

--September 10, 1971

Nixon: Bob, please get me the names of the Jews, you know, the big Jewish contributors of the Democrats. All right. Could we please investigate some of the cocksuckers?

--September 13, 1971

Nixon: Is [Arthur Bremer, who had just shot and crippled presidential candidate George Wallace] a left winger, right winger?

Colson: Well, he's going to be a let winger by the time we get through, I think.

Nixon: Good. Keep at that, keep at that.

Colson: I just wish that I'd thought sooner about planting a little literature out there.

--May 15, 1972

In an attempt to gain even more control over the Agency and possibly even survive the Watergate revelations, Nixon appointed James R. Schlesinger to the position of Director of Central Intelligence. Schlesinger immediately fired fifteen hundred Agency employees, two-thirds of whom worked in operations. In May 1973, he and Deputy Director of Operations and former Phoenix Program architect William Colby directed that all present and past employees report any illegal activities of which they knew to the new Director. Schlesinger also fired John Huizenga from the Office of National Estimates, a department staffed with veterans of the OSS. Schlesinger's reward after only four months service was to be "promoted" to Secretary of Defense. William Colby became the new Director.

Ehrlichman: One marginal piece of news that they brought in that has Colson a little shook is that McCord has told the U.S. Attorney that he participated in an operation with Hunt to go out to Las Vegas, leave their airplane with the engines going standing by, go into town, bust reporter Hank Greenspun's safe--

Nixon: Jesus Christ!

Ehrlichman: Yes--steal some stuff from it, jump back in the airplane, and come on back, and that Colson masterminded it.

--April 13, 1973

It is also interesting to consider the degree of public concern in the affair. The media today is quick to point out that the public took very little initial interest in the great scandals of the last fifty years--Watergate, Iran-Contra, October Surprise, Whitewater--but the level of interest of the media itself--and a willingness to explain what it is about certain events that should be important to people who have been told they live in a democracy--is a far better predictor of public concern. After all, if the public can be misled into believing that something as trivial and idiotic as the Academy Awards Fashions Show is a burning social issue, they can certainly come to accept attempts to overthrow the electoral process as being at least marginally important. When the parade of perjurers, obsctructionists and self-serving confessors began appearing before Senator Sam Ervin's televised Watergate Committee in the late spring of 1973, most Americans knew very little about the subject under consideration. No particular storyline had emerged to make the issues significant, and so despite a long history of unethical dealings, Nixon and his men did not stand instantly accused. Besides, anyone sufficiently knowledgeable about Nixon's activities would have of necessity known how severely his administration dealt with dissent. That is why only after the honor of the White House began to crumble did it become safe to criticize.

It is possible with some degree of accuracy to isolate the moment that safety presented itself. James McCord testified to the Senate Committee on March 28, 1973. he named John Mitchell, Charles Colson, Jeb Magruder and John Dean as Watergate conspirators. The response from key Republicans was immediate. Vice President Spiro Agnew, Republican National Committee chairman George Bush and Senator Barry Goldwater all urged the President to counteract the allegations. Nixon's response was that he would permit his White House staff members to appear before the senate Committee, as well as to testify before the grand jury. As a result, John dean hired himself an attorney. Richard Nixon began praying he would not wake up the next morning.

Agnew was having problems of his own. The U.S. Attorney in Baltimore was investigating allegations of tax evasion regarding friends of Agnew when he had been Maryland's governor. Rumors of bribes abounded. In August 1973, the investigation hit the pages of The Wall Street Journal. The newspaper repeated reports that Agnew had continued taking bribes even after moving into the White House. The Vice President insisted these allegations were damned lies. It turned out Agnew was the damned liar. Shortly after resigning he plead no contest to tax evasion and was rewarded with a small fine and suspended sentence. His replacement was Gerald Ford.

Meanwhile, the President was going nuts. Ordered to obey a subpoena by Special Prosecutor Archibald Cox, Nixon sneered and instructed Attorney General Elliot Richardson to fire the Independent Counsel. Rather than comply, Richardson resigned. Deputy AG William Rucklehaus was given the same order and also resigned. Cox was nevertheless ultimately discharged.

In response to the behavior of the emotionally unstable Nixon, OPEC announced a boycott of oil sales to America, an act which coincided with a decade of oil industry deregulation in the United States. As a direct result of these two factors, oil prices quadrupled.

In the Middle East, the Yom Kippur War raged and Soviet troops made tentative gestures in the direction of Israel. U.S. forces went on nuclear alert.

Lost somewhere between stunned disbelief and cynical reaction, America faced the prospect of admitting its own devaluation. As Ho Chi Minh's forces united Vietnam, the illusion that the United States enjoyed world wide prestige could no longer be maintained. When the follower's of Iran's Ayatollah Khoimeni seized the U.S. embassy in Tehran, the fifty-two hostages were not so much prisoners as they were American phallic symbols wilting in the ill winds of political upheaval. Neither Presidents Ford nor Carter were able to stimulate the erection of the heart that the public didn't even know it needed until Ronald Wilson Reagan convinced them that such was so. This stiffening would in fact come about with the ascension of the John Wayne of politics, an ascension that dragged America deeper into a hellfire darkness.

—were members of the same karass, a concept written about by Kurt Vonnegut in Cat’s Cradle, wherein the author describes karass thus:

—were members of the same karass, a concept written about by Kurt Vonnegut in Cat’s Cradle, wherein the author describes karass thus:

.jpg)