THE TRIBE

German-born America Johann Most found acceptance as a young man with socialist workers both in Europe and in America. Tormented by a facial disfigurement, Most moved to the United States in 1882 and brought his newspaper, Freiheit(freedom), with him. An inspiring writer with a wicked sense of humor, Most advocated revolution through the actualization of ideas, e.g., through violence. His best-known writing, a pamphlet called “The Science of Revolutionary Warfare: A Little Handbook of Instruction in the Use and Preparation of Nitroglycerin, Dynamite, Guns, Fulminating Mercury, Bombs, Fuses, Poisons, Etc.,” did not become a bestseller, although it did succeed in getting him labeled as a firebrand.

Johann Most

It was around this same time—specifically, 1886—that a young and heretofore unknown printer named Henry George wrote a book which—according to his granddaughter, Agnes George de Mille—made him the third most famous man in the United States, right behind Thomas Edison and Mark Twain. His book, Progress and Poverty, was praised by Leo Tolstoy, John Dewey, and George Bernard Shaw, among others. As de Mille summarizes the basic thrust:

The nation is no longer comprised of the thirteen original states, nor of the thirty-seven younger sister-states, but of the real powers: the cartels, the corporations. Owning the bulk of our productive resources, these multinationals are not American anymore. Transcending nations, they serve not their country’s interests, but their own. It is the insidious linking together of special privilege that produces unfair domination and autocracy. He who makes should have; he who saves should enjoy; what the community produces belongs to the community.

Also interested in wealth and poverty was a young man named Albert Parsons. He and his wife Lucy moved to Chicago in 1872. Convinced that the rich and powerful willingly wronged the poor and weak, and opposed to this, he joined the Workingmen’s Party of the United States just in time for the Great Railway Strike of 1877. According to his autobiography, 30,000 workers gathered on Market Street where Parsons spoke, advocating the nationalization of “all means of production, transportation, communication and exchange, thus taking these instruments of labor and wealth out of the hands of private individuals, corporations, monopolies and syndicates.”

Albert Parsons

Over the next few years, Parsons found that his radical pronouncements infringed upon his ability to find meaningful employment. Such being the case, he and his colleagues had nothing to lose and renamed their organization The Socialist Labor Party. Convinced that “the government and its laws were merely the agents of the owners of capital to reconcile, adjust and protect their—the capitalists’—conflicting interests,” Parsons threw himself into the movement for an eight-hour workday. This involvement culminated in what came to be called the Haymarket Tragedy. The matter was a simple one: Workers wanted a reduction in their work hours without a reduction in their pay. Failing this, they would strike. The ensuing walk-out revealed 350,000 workers joining the mass general strike. 40,000 of these workers were in Chicago, many of them at the McCormick Harvest Works. The date was May 3, 1886. Police fired into the crowd of unarmed strikers, killing four men. The following day the leaders of the local strike called a meeting atHaymarket Square to consider the workers’ response to the shooting. Again the police arrived and this time someone threw a bomb which killed one policeman. The cops struck back with vengeance, arresting anyone suspected of being a radical. Eight men, including Albert Parsons, were charged with the bombing. Parsons described the scene:

A large number (over 3,000) citizens peaceably assembled to discuss their grievances viz: the 8-hour movement and the shooting and clubbing of the lumberyard strikers by the police the previous day. After 10 o’clock when the meeting was adjourning, two hundred armed police in menacing array, threatening wholesale slaughter of the people there peaceably assembled, commanded their instant dispersal under pains and penalties of death. A person unknown threw a dynamite bomb among the police.

Parson’s wife Lucy was not dormant during this time. The eight men having been found guilty, Mrs. Parsons led a campaign for clemency. Traveling across the country to gather support, she usually found police waiting for her wherever she went. Once she realized her husband would indeed be executed for a crime for which in all likelihood he did not participate, she took her two children with her to see Albert one last time. Rather than permit this, the police arrested Lucy and her children, stripped them naked and left them in a cell until Mr. Parsons had been hanged. Dazed but undaunted, she continued to promote the revolution, selling copies of her booklet Anarchismto interested parties. Although she differed with many radicals of her day on the issue of free love (Lucy being very much in favor of marriage), she remained an advocate for freedom and workers’ rights until her death in 1942.

Another woman in the anarchist ranks was Emma Goldman, a Russian-born immigrant who gained fame as an American radical. Although Goldman advocated birth control and other women’s rights, the larger issue of anarchy was her passion. In her book, Anarchism and Other Essays, she defined the term.

Anarchism: The philosophy of a new social order based on liberty unrestricted by man-made law; the theory that all forms of government rest on violence, and are therefore wrong and harmful, as well as unnecessary. Anarchism is the only philosophy which brings to man the consciousness of himself; which maintains that God, the State, and Society are nonexistent, that their promises are null and void, since they can be fulfilled only through man’s subordination.

Emma Goldman

If expressing such sentiments was not sufficient provocation for her unlawful arrest, she did serve time for encouraging the destitute to steal food, for lecturing about birth control, and for decrying military conscription. Eventually Goldman, her longtime friend Alexander Berkman, and 247 others were deported to Russia aboard the Soviet Ark.

Somewhat less radical than Goldman, but still wild for all that, was Daniel de Leon, a native of Curacao and a U.S. immigrant. De Leon, as the editor of the socialist newspaper The People, helped create the Socialist Trade and Labor Alliance as an alternative to the far more conservative American Federation of Labor. In June 1905, he and several other trade unionists met inChicago where they formed the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), or as they were sometimes known, the Wobblies. Present at this inaugural meeting was the aforementioned Lucy Parsons, Bill Haywood, Mother Jones, Charles Moyer and Eugene Debs. De Leon might have been thinking of Lucy Parsons when he said, “Why should a truly socialist organization of whites not take in Negro members? On account of outside prejudice? Then the body is not truly socialist? A socialist body that will trim its goals to outside prejudices had better quit.”

Strikes served as more than a method for radical workers to exercise their power. Sometimes the strikes were radicalizing experiences in and of themselves. One such was the Pullman Strike of 1894. George Pullman erected a company town which was superficially benign but inherently malignant. Famed attorney Clarence Darrow related the events leading up to the clash:

George Pullman, the sleeping car man, had built a new town out of five hundred acres ofIllinois prairie to house his workers. An extraordinary place. Listen to how he described it: “Bright beds of flowers and green velvety stretches of lawn dotted with parks and pretty water vistas. Homes filled with light. A town where all that inspires to cleanliness of person and thought is generously provided.” I almost bought a home there myself. The main street was a vision: bright red flower beds, rows of tall green trees lining the walks, houses of neat red brick with trim lawns. Lovely. Only—and this was curious—one street back from the main street, where the workers lived, the houses didn’t have lawns. They didn’t have windows. They had, at most, one faucet, for cold water, and that was in the basement where it was cheapest to run the pipes. Five families crowded into each tenement, all using one toilet. In the entire town where “everything that inspires to cleanliness of person is generously provided,” not one bathtub.

Clarence Darrow

On the surface, it seemed a paradise: workers could walk to work each day, housing was furnished, and they could buy groceries and other essentials right there in Pullman City. The larger, dark side of the story was that in order to work for the Pullman Palace Car Company, they had to live in the company town and buy the services, were required to smile about increased work loads and pay cuts, and even had to pay rent for using the company church. As Martina Brendel tells the story:

On May 11, 1894, three thousand Pullmanworkers went on a wildcat strike. Many of the strikers belonged to the American Railroad Union (ARU) founded by Eugene Debs. Some ARU members refused to allow any train with a Pullman car to move. The twenty-four railroads that were part of the General Managers Association tried to end the strike. They announced that any switchman who refused to move rail cars would be fired. By June 29, fifty thousand men had quit their jobs. Crowds of people who supported the strike began stopping trains.

The railroads sent in strikebreakers and scabs. The striking workers began tearing up tracks and burning railway cars. President Grover Cleveland, committed to the General Managers Association, sent in federal troops to end the strike. Outraged, the workers smashed switching stations and burned cars to the ground. The troops began shooting the rioters. Rather than risk more workers being killed, Debs ended the strike. Subsequently, the ARU leader was charged with contempt of court. Although Debs found representation from Darrow, he was found guilty and served six months in jail.

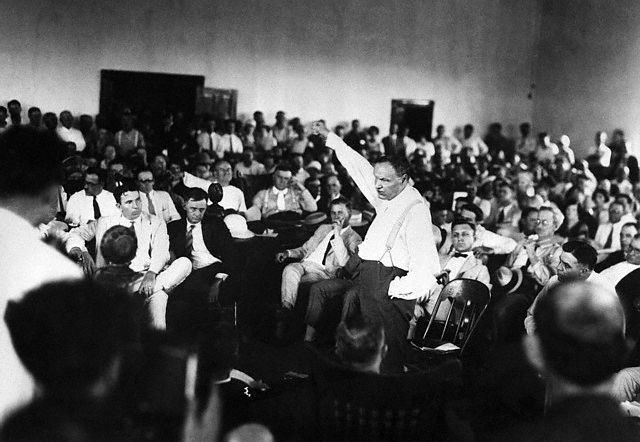

Eugene Debs

Debs was not finished with political action. Also, he was not finished with being incarcerated. As a charter member of the Socialist Party of America, Debs ran for President of the United States in 1904 and received 400,000 votes. Four years later he ran again, getting 420,000 votes. In 1912 he and running mate Emil Seidel netted 890,000 votes. Seidel may be remembered as the first socialist mayor of a major city in the United States,Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

In June 16, 1918, Eugene Debs made a public speech in Canton, Ohio, a speech wherein he complained about the then recently-employed Espionage Act, a speech which landed him a ten-year prison sentence. Here is part of what he said that day:

They sentenced Kate Richards O’Hare to the penitentiary for five years. Think of sentencing a woman to the penitentiary simply for talking. The United States, under plutocratic rule, is the only country that would send a woman to prison for five years for exercising the right of free speech. If this be treason, let them make the most of it. Rose Pastor Stokes! Here we have another heroic and inspiring comrade. Did her wealth restrain her an instant? She went out boldly to plead the cause of the working class and they rewarded her high courage with a ten year sentence.

Debs was in the Atlanta Correctional Facility serving his sentence when, in 1920, he received more than 900,000 votes for his final candidacy for President.

The actual cause of both the oppression and the rebellion was the single greatest technological advancement relating directly to America’s Manifest Destiny: the completion in 1869 of the transcontinental railroad, for which there was no shortage of rail lines ready to transport. The Union Pacific, the Central Pacific, the Northern Pacific, the Southern Pacific and the Santa Fe all had reached the west coast by the mid-1880s. The most immediate consequence was that it no longer required months to cross the nation. If one could endure a few days monotony, one could go from east to west, which was by far the direction of choice. The increase in population of western states between 1880 and 1960 is instructive. The states of Washington, Oregon and Idaho had a collective population in 1880 of 282,000. Thirty years later the same area held 2,000,000. And fifty years after that it was 5,300,000. Contrast this with the decline in the population of American Indians. In Oklahoma Territory in 1880, there were better than one million Indians and not one Anglo. By 1960, there were only 55,000 Indians and more than two million Europeans.

As far back as the Civil War, a young artist named Thomas Moran had been fascinated by the brushwork of an English artist named J.M.W. Turner. The latter had a knack for rearranging the scenery of a locale while still representing the essential essence of that place. That fit. Even though Moran’s replications of the new frontier would urge on a massive migration of people toWyoming, Colorado and California, the magnificence of his style not only served to preserve nature in paint, but also gave an impetus for the land preservation movement to save a bit of the past for posterity. After all, the 1890 Census had concluded that there were no more frontiers! This was less than twenty years after Congress declared Yellowstone America’s first national park. Already the United States was worried it would run out of room, but it also feared a loss of those things—like natural beauty—that had lured so many to it in the first place. Perhaps that is why Moran’s paintings rarely included evidence of the railroad itself. Congress bought two of his finest works for display in the Capitol Building: Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone and Chasm of the Colorado.

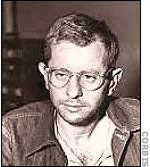

The same year that Moran retired—1892—Thomas Mooney was born. By age fifteen he was already winning writing contests for socialist magazines and in his twentieth year he was chosen as editor of Revolt. Not one to sit by as heroes such as Eugene Debs fomented revolution, Mooney was accused by the San Francisco Police of blowing up part of Pacific Gas and Electric, but after his third trial, he was finally acquitted. A few years later, in 1916, a bomb exploded at the United Railroads of San Francisco, killing several men. Dan Georgakas tells of the aftermath:

When the fatal bomb went off on 22 July, the Mooneys were blocks away, but both Tom and his wife Rena, Warren K. Billings, Israel Weinberg and Edmund Noland were arrested. Ultimately only Tom Mooney and Warren Billings were convicted, Mooney for first degree murder and Billings for second degree murder. In less than a year, solid evidence began to surface that the testimony against Mooney and Billings had been perjured. Other evidence substantiated their own account of where they had been. Mooney was officially pardoned in 1939, but Billings would not be officially pardoned until 1961.

Tom Mooney

All of these folks—Johann Most, Henry George, Albert Parsons, Lucy Parsons, Emma Goldman, Daniel De Leon, Eugene Debs, Thomas Moran and Tom Mooney

—were members of the same karass, a concept written about by Kurt Vonnegut in Cat’s Cradle, wherein the author describes karass thus:

—were members of the same karass, a concept written about by Kurt Vonnegut in Cat’s Cradle, wherein the author describes karass thus:We Bokonists believe humanity is organized into teams, teams that do God’s Will without ever discovering what they are doing. Such a team is called a karass by Bokonon. “If you find your life tangled up with somebody else’s life for no very logical reasons,” writes Bokonon, “that person may be a member of your karass.” Hazel’s obsession with Hoosiers around the world was a textbook example of a false karass, of a seeming team that was meaningless in terms of the ways God gets things done.

There was never any mention of the karass by the aforementioned radicals, in no small part because the concept had not been formalized while these people still walked the earth, a fact which not only does not exclude these people from membership but which also allows this particular karass to include Bill Haywood, Clarence Darrow and John Scopes.

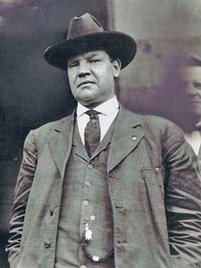

Big Bill Haywood

Radicalized by both the Pullman Strike and the Haymarket slaughter, Big Bill Haywood was primed for adventure. At the turn of the twentieth century, Haywood and a somewhat more diplomatically predisposed individual named Charles Moyer shared leadership of the Western Federation of Miners (WFD), where they advocated an eight-hour workday at a time when the mine owners expected the employees to commit to a ten hour day, thirteen days out of fourteen. Haywood’s native Utah became the first state to grant an eight-hour day for its miners.

The methods of the WFM were not always peaceful ones. In June 1904, the Colorado Labor Wars between the miners and the owners saw a great deal of bloodshed, with thirteen non-union members killed by a bomb as they waited for a train. Just before Christmas of the following year, former Idaho Governor Frank Steunenberg came home from work and was blown apart by yet another bomb. The police arrested Harry Orchard, who confessed to being a hit man hired by the WFM. Orchard named Haywood, Moyer, and a former board member named George Pettibone as having ordered the hit. Pinkerton detectives kidnapped the three men in Denver and returned them to Boise, Idaho. Clarence Darrow took on Haywood’s defense, winning an acquittal. Exhausted by Moyer’s waffling, Haywood left the union.

But Big Bill did not rest. Instead, he threw himself into the IWW, an organization that approved of his yearning for direct action. As Paul Buhle wrote in Monthly Review:

The IWW was the “greatest thing on earth,” according to its members and devotees. It averaged, in its nest years, perhaps a hundred thousand members. Yet it brought together the poorest and most downtrodden working people from every race and group. Industrial unions were, in the Wobbly vision, to be the building blocks for the future cooperative society. Working people who understood their own power had the capacity to act upon their fundamental right to expropriate and share with other workers across the world everything that they collectively produced.

Perhaps the International Workers of the World’s biggest coup came with the strikes of 1912 and 1913 in Massachusetts and New Jersey, respectively. In these environments IWW organizers established soviets, or workers councils, composed of formerly transient workers and others on the low end of the labor spectrum. This was Haywood’s mission, and through direct action, he accomplished it.

Haywood’s opposition to World War I landed him in trouble with the administration of President Woodrow Wilson. Once he called for a strike as a method of defeatism, federal authorities locked him up. Released on bail, he fled to theSoviet Union where he eventually died. Half of his ashes were interred in the Kremlin and the other half near the Haymarket tragedy.

Labor’s favorite attorney, Clarence Darrow, had at one time represented the city of Chicago, as well as the North Valley Railway. But Darrow’s liberal views overpowered his sense of obligation to big business and he ended up defending not only Eugene Debs and Bill Haywood, but many others held in disrepute. Near the end of his legal career, Darrow agreed to represent John Scopes in the state of Tennessee’s trial against a teacher who, in 1925, dared to teach the fact of evolution. William Jennings Bryan, who considered himself a progressive thinker, led the prosecution. The entire trial was in large part a publicity stunt, with the local board of education on the side of evolution and the prosecution on the side of the Bible as the literal word of God. Doug Linder recalls an amusing exchange when the defense calledBryan to the stand.

Bryan, who began his testimony calmly, stumbled badly under Darrow’s persistent prodding. At one point the exasperated Bryansaid, “I do not think about things I don’t think about.” Darrow asked, “Do you think about the things you do think about?” Bryanresponded, to the derisive laughter of the spectators, “Well, sometimes.”

Darrow asked at the end of his summation that the jury please find his client guilty so that they could appeal the decision to the Tennessee Supreme Court. Since both prosecution and defense wanted a guilty verdict, the jury accommodated and Scopes was fined $100. The defendant himself wrote: “I was convicted of the crime of teaching the Darwinian concept of evolution. H.L. Mencken, acting on behalf of theBaltimore Evening Sun, paid my fine.”

Connections ran through the lives of these men and women and no doubt through those of many others. Passion for the working class or for the put-upon is obvious, as is a somewhat molten desire for the “truth.” But the super-connection is a bit less obvious. For one thing, all of these members of the karass would have had a much easier time with life had they chosen almost any other conceivable path. Despite their fame, or because of their infamy, none of them were made to feel particularly welcome in their own country. All of them went up against forces far larger than themselves and all of them frequently lost. None of them, however, let their defeats defeat them. More significantly for the purposes of the halcyon tribe, these revolutionaries made possible the actions more than a generation later for a cultural upheaval the likes of which the United States had never seen.

Charlotte Gilman

Members of the same karass also included Charlotte Gilman, Alice Paul, Jeanette Rankin and Francis Perkin, all feminists, all to one degree or another suffragettes, and all American women who cared passionately about equality for all people.

Charlotte Gilman gained both fame and notoriety for her literature, theories of economics and public lectures. In the final years of the nineteenth century, she edited The Impress, a feminist literary periodical wherein she contributed her own stories written in the voice of contemporary celebrated authors. She also published a book of her own satiric poetry called In This Our World. Economically, she favored utopian socialism. Politico-sexually, she recommended parthenogenesis. And extemporaneously, she renounced the divisions between women and men. Petri Siukkonen summarizes her views:

She attacked the old division of social roles. According to Gilman, male aggressiveness and maternal roles of women are artificial and not necessary for survival anymore. “There is no female mind. The brain is not an organ of sex. One might as well speak of a female liver.” Only economic independence could bring true freedom for women and make them equal partners to their husbands.

Far more radical was Alice Paul, whose well-to-do upbringing on a farm called Paulsdale, spanned the nineteen and twentieth centuries. A devout Quaker, she believed in gender equality and was committed to the overall improvement of society, as well as to the value of a back-to-nature lifestyle. A trip to England in 1907, where she encountered violent opposition to British suffrage, politicized the young Ms. Paul, so when she returned to the United States three years later, she joined the National American Women’s Suffrage Association (NAWSA). Rebecca Carol picks up the story:

Alice Paul and two friends, Lucy Burns and Crystal Eastman, headed to Washington D.C.to organize for suffrage. They organized a publicity event to gain maximum national attention: an elaborate and massive parade by women to march up Pennsylvania Avenue and coincide with Woodrow Wilson’s presidential inauguration. The scene turned ugly, however, when scores of male onlookers attacked the suffragists, first with insults and obscenities, and then with physical violence, while the police stood by and watched.

Disgusted by NAWSA’s support for Wilson, Paul formed the National Woman’s Party (NWP), a group which did such a good job of picketingWilson that the police arrested them for obstructing traffic and jailed them in Virginia’s Occoquan Workhouse. The jailed NWP members viewed themselves as political prisoners and staged a hunger strike. This behavior was met by the jailers with beatings of the women, most of whom were locked up in unheated and rodentially-populated cells. Public sympathy was on the side of the suffragettes and so they were ultimately released. This public pressure led Congress to pass the Nineteenth Amendment which, after three-fourths of the states ratified it, gave women the right to vote.

A bit less out of the mainstream in her tactics, if not in her beliefs, was Jeanette Rankin, who in 1916 became the first female member of the House of Representatives. A Republican, Rankin voted against the United States entering World War I and lost her re-election bid two years later. As a private citizen, she marched in favor of theMaternity and Infancy Protection Act (1921),Independent Citizenship (1922), and the Child Labor Amendment (1924). In November 1940, she ran again for Congress and won, but her lone vote against declaring war on Japan doomed her political career.

Another member of the karass was Frances Perkins, who became politically aware in 1911, when, as the AFL-CIO website describes it:

She watched helplessly as 146 workers, most of them young women, died in the Triangle Waist fire. Many, she remembered, clasped their hands in prayer before leaping to their deaths from upper-floor windows of a tenement building that lacked fire escapes.

A firm believer in working within the system, she took an appointment with the New York State Industrial Commission, becoming, under future-President Franklin Roosevelt, the head of the commission.

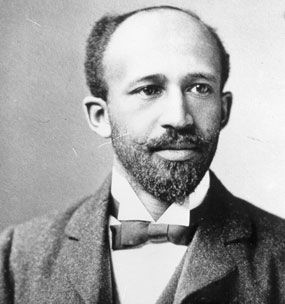

Equality between women and men is not the only historical and progressive karass in new American history. People who worked actively in what was eventually called the Black Power Movement were part of a politically and historically interwoven set of tribes whose common purpose was an end to the oppression of African-Americans, as well as a strengthening and growth of black people throughout the world. As with women’s suffrage, black emancipation is difficult to pinpoint in its precise origins, and any list of important people in this movement will no doubt omit some who were crucial. Among people who through their viewpoints, actions and accomplishments must not be ignored include W.E.B. DuBois, who, as Gerald Hynes correctly accesses, is one of the fathers of social science.

W.E.B. DuBois

William Edward Burghardt DuBois, concluding his fellowship at the University of Pennsylvania in 1896, wrote The Philadelphia Negro, which put a human face on the dislocation of American blacks within an historical framework. Moving ontoAtlanta University, DuBois continued writing and research, validating the notion that the study of the “Negro problem” was a legitimate field of sociological endeavor. As editor of the NAACP’s magazine Crisis for a quarter century, DeBois’ writings inspired the creation of a black officers’ training school, legal action against lynchings, and a federal work plan for returning black veterans. After traveling to Russia in 1927, DuBois radicalized himself and within a few years left the NAACP, returning to academia. Back at AtlantaUniversity, he wrote Black Reconstruction (1935) and Dusk of Dawn (1940). As Hynes picks up the saga:

As the chairman of the Peace InformationCenter, he demanded the outlawing of atomic weapons. The U.S. Department of Justice ordered DuBois and others to register as agents of a “foreign principal.” DuBois refused and was immediately indicted under the Foreign Agents Registration Act. DuBois was acquitted. On August 27, 1963, on the eve of the March on Washington, he died in Accra,Ghana.

After World War I, black Americans returned home alongside their white counterparts. Having lived and died fighting to enrich their common masters, blacks anticipated that the conflict would unify Americans of all races. When the sons and grandsons of emancipated slaves still found themselves treated as third-class citizens, many joined the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), a Black Nationalist organization founded by Marcus Garvey. As one of the largest mass movements in U.S. history, by the early 1920s Garvey’s group had seven hundred branches in thirty-eight states. As David Van Leeuwen has written, “For Garvey, it was no less than the will of God for the black people to be free to determine their own destiny.” The solution, felt Garvey, was to return to Africa. By combining unity, pride and autonomy, African-Americans could become a mighty race. Unlike the labor movement that preceded and overlapped his own life, Garvey was no enemy of capitalism, and even gained support from the countries of Liberia andSierra Leone, as well as the Ku Klux Klan in heralding a “Back to Africa” movement, in which Garvey’s own company, the Black Star Line, would ship black people back home. Once Garvey began proclaiming that Jesus was black, the U.S.government stepped in and indicted him for mail fraud. Immediately after his release from prison, the government deported Garvey to Jamaica.

Marcus Garvey

An even more enduring black separatist organization is the Nation of Islam, or the Black Muslims. Founded in Detroit in 1930 by Wallace Fard, the Black Muslims believed their success mandated removal from white society. Under the leadership of Elijah Muhammed, the Nation of Islam bought substantial plots of land deep in the southern United States. As God’s chosen people, the Black Muslims rejected the use of illegal drugs, developed their own paramilitary army, and yearned for their own separate nation. In 1975, Elijah Muhammed died. The Nation of Islam splintered and the Black Muslims offered their leadership to Louis Farrakhan.

Certainly the largest and most fearsome black paramilitary force in the United States was the Black Panther Party, formed in October 1966 by Huey Newton, Bobby Seale and David Hilliard. Tired of the nonviolent approach of Martin Luther King’s Southern Christian Leadership Committee, the Panthers took the position that most oppressed people had one thing in common: their enemy was the United States government. Indeed, the Black Panthers had reason to feel persecuted. While they organized breakfast programs that fed thousands of hungry children throughout the country, Huey Newton and Bunchy Carter were shot dead by assassins in Los Angeles and Fred Hampton and Mark Clark were slaughtered inChicago.

Less violent but just as committed to social justice was the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). The brainchild of an interracial group of no hierarchically-inclined University of Chicagostudents in 1942, CORE is perhaps best recalled for its organization of the Freedom Rides in the early 1960s. In the case of Boynton v. Virginia (1960), the U.S. Supreme Court deemed unconstitutional the segregation of interstate bus and rail stations. CORE decided to test the ruling and so on May 4, 1961, seven blacks and six whites departed on buses headed south. Winston Blacktop relates:

In the second week the riders were severely beaten. Outside Anniston, Alabama, one of their buses was burned, and in Birminghamseveral dozen whites attacked the riders only two blocks from the sheriff’s office. On their arrival in Montgomery they were savagely attacked by a mob of more than 1,000 whites.

Sympathetic members of the media reported on this brutality and by 1964 thousands of college kids had joined CORE. The organization singled out the state of Mississippi for its violent propensities and refusal to allow blacks to vote.

Thirty-seven black churches and thirty black homes and businesses were firebombed or burned that summer, and the cases often went unsolved. More than 1,000 black and white volunteers were arrested and at least eighty were beaten by white mobs or racist police officers.

The murders of Andrew Goodman, James Chaney and Michael Schwerner in June of that year changed everything. These CORE civil rights workers were murdered with the complicity ofMississippi police officers, an event discovered six weeks after their disappearance and one which mobilized a previously recalcitrant Johnson Administration into supporting civil rights.

The Tate-LaBianca murders were committed by members of the Manson Family one week before the Woodstock Festival. Although these two events occurred at opposite ends of the country, mass communication brought the reality of these two perverse celebrations as close as next door. Certainly the stupid violence at the Altamont Raceway a few months later did nothing to quell the idea that young America had no sense at all. The subsequent arrests, trials and convictions of the Manson Family further discredited the propriety of youth’s alternative lifestyle: drugs, free love, long hair, racial harmony and radical politics—these could all be superficially tolerated by Nixon’s Silent (frightened) Majority. But a series of violent murders committed to ignite a race war was too bizarre to accept. Once the images of the killers were broadcast over television and displayed in newspapers and magazines, the children of World War II were no longer presumed naïve.

Mass murderers had heretofore been either one-man operations or the domain of organized crime. In the first two decades following the resolution of World War II, the image of the “lone nut” was engraved on America’s consciousness.

Sharpshooter and Bible-thumper Howard Unruh picked up his 9mm Luger on September 6, 1949 and twelve minutes later, thirteen family members, friends and total strangers lay dead in Camden, New Jersey. Unruh’s motive was blind retaliation for the theft of a fence that he used to keep out the rest of the world.

Droopy-eyed Billy Cook kidnapped the five-member Carl Moser family on New Year’s Eve 1950, killing each of them while in route to Joplin, Missouri. A salesman named Robert Dewey was killed by the same yung man.

Walking death machine Melvin Rees began a spree of murders and rapes in Maryland in 1957. By the time he was caught—four years later—he had destroyed nine people, mostly female children.

During this same time period, Harvey Glatman raped and murdered three Los Angeles women. He was executed for his crimes.

Charles Starkweather slaughtered eleven people out of a sense of boredom and frustration.

In Chicago in 1966, Richard Speck murdered eight nurses while a ninth hid under the bed.

Marine Corps graduate Charles Joseph Whitman killed his mother and father and the next day climbed the tower at theUniversity of Texas in Austin and shot forty-six people, sixteen of whom died.

Al of these people were men under the age of thirty-five, all were loners and social misfits, and all channeled their antisocial proclivities in violent ways. Unlike these men, Charles Manson had his own loosely-knit gang of highly motivated disciples to act out his violent impulses for him. For reinforcement he used isolation, drugs, religion, and a unique interpretation of Beatles songs, just as those in power in the United Statesused the isolation inherent in the vastness of the country, the drugged effects of television, religion and the mass media to program its citizenry.

While it would be historically inaccurate to claim that the Manson Family brought an end to the counterculture, it is true that the Family contaminated every area of society with which it made contact. Nothing so emphasized the magnitude of this contamination as the publication of a book in November 1974.

Helter Skelter was the most frightening book ever written in the genre of what came to be called “true crime.” Former Deputy District Attorney Vincent Bugliosi’s story of the Manson murders began with a page that simply said: “The story you are about to read will scare the hell out of you.” That admonition was not hyperbole. It was the truth. With co-author Curt Gentry, Bugliosi drove the reader screaming around corners and down stairwells with his foot through the floorboards. Even the more philosophical sections brought the totality of the dread moaning down over the reader’s ears. This effect was enhanced by the suggestions that some of the killers were still on the loose and that when those who had been apprehended were released from prison they would leave the streets slippery with blood.

For his midnight missions, Manson chose people in their late teens and early twenties. Although Manson and his disciples were politically reversed from the protestors in Chicago at the previous year’s Democratic National Convention, they did share a sense of community, long hair, no particular aversion to illegal drugs and a disregard for the sexual mores of the Silent Majority. While Tom Hayden, Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin denied the Chicago demonstrators had any kind of leadership, Manson was the unquestioned head of his group. Whereas the Yippies were not autocratic and had goals that often contradicted one another, as the sole leader of his Family, Manson’s goals were quite clear. And so with images of bare-chested boys torching flags pulsating in the collective consciousness, America was undone by nightly news viewings of the nomadic tribe that seemed to speak of affluence in disarray. While the news reports of the kill-cult were book-ended with body counts from Vietnam, whatever instincts toward cohesiveness for which Americans yearned were fractured by the very informational access which united them in their divisive fear. To the television screen, bare feet and long hair all looked the same.

In December 1969, the same month the arrests of the Manson Family were made public, the Rolling Stones declared a free concert to be held near San Francisco. Twenty-four hours before it was scheduled to begin, Altamont Raceway, which comfortably accommodated 6,500 people, was announced as the site. 300,000 people whose idea of freedom was not having to pay for anything showed up to hear the Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane, Crosby Stills and Nash, and the headliners: The Rolling Stones. Security for the concert was provided by the Hells Angels in exchange for $500 worth of beer. That the Rolling Stones had the slightest concern for the safety of their fans is doubtful. That they were even concerned for themselves is measured by the fact that they were guarded by a group of drunken violence freaks. “Brothers and sisters, please!” singer Mick Jagger pleads in the film of the concert, Gimme Shelter. It did not good for audience member Meredith Hunter, He was beaten and stabbed to death right on camera. The media soaked up the story and squeezed it out all over the world. So as the 1960s came to an end, youngAmerica appeared badly out of even its own control.

Into this whirlwind strolled buckskinned Charles Manson and his loyal salivating sycophants, Susan Atkins, Patricia Krenwinkel, Leslie van Houten and Charles Watson. In addition to the nightly television coverage, several national magazines publicized the story with enthusiasm.Tuesday’s Child, Rolling Stone, Life and evenLadies Home Journal ran feature stories. Susan Atkins had no more than finished testifying to the grand jury when Lawrence Schiller published a dollar paperback called The Killing of Sharon Tate. The trial was scarcely over when Fugs member Ed Sanders released a book called The Family, which, after Schiller’s book, read like The Great Gatsby. Robert Hendrickson completed a documentary called Manson, but by the time it was released, hippie was dead, Yippie was underground, and most of the “longhaired freaky people” had either joined the KKK or else gone on to make a difference on Wall Street.

“The story you are about to read will scare the hell out of you.”

Bugliosi did not limit himself to the story of the murders and his crucial role in getting the convictions. He went much deeper into the abyss. For one thing, the seven Tate-LaBianca victims were not the only people killed by the Family. Gary Hinman, Donald Shea and John Haught were all slain before the trial began. Bugliosi strongly suggested and today still believes the Family murdered van Houten’s attorney Ronald Hughes. Bugliosi offered a mix of evidence and speculation that the Manson clan killed ten other people between October 1968 and November 1972, for a total of twenty-one. “Are there more?” Bugliosi asked. “We tend to think that there probably are, because these people liked to kill.”

President Gerald Ford was stumbling amidst theSan Francisco public one autumn day in 1975 when a young redhead stepped through the curious crowd of well-wishers and aimed her gun at the President of the United States. The weapon jammed and as the Secret Service tackled the young woman, she screamed, “It wasn’t loaded!”

Lynette “Squeaky” Fromme, proud dues-paying member of the dwindling Manson Family, was sent to prison. For the second time within a month, Ford had nearly been assassinated, the nation was spared the horror of a Nelson Rockefeller Presidency, and the Family was back in the news. Squeaky appeared on the covers of both Time andNewsweek.

The following year, Helter Skelter was released as a two-night television movie, a PG version of which later became available on home video. Despite having none of the flair of the book and in Steve Railsback the worst characterization of Manson short of the wax figure at Madame Tousaud’s, the shows were at the time the most-viewed programs in television history. Susan Atkins and Charles Watson converted to Christianity and wrote books about it. Manson appeared on several TV shows and even gave an interview to Geraldo Rivera, wherein the latter’s ego was finally matched. A collection of Manson’s writings was published. The Family’s record albums are collectors’ items.

The true allure of the Manson lore may be as simple and profound as something the late Paul Watkins wrote in his own autobiography. Manson’s former second-in-command and chief procurer stated: “Charlie did more than give hitchhikers and hippies a bad name. He manifested and expressed not only the mechanism of his own twisted psyche, but the latent evils existing within our own society.”

* * * * * * * * * * * *

He had been acquainted with a man named Donald DeFreeze, and had suggested that DeFreeze take the name Cinque. He had helped lay plans that resulted in the kidnapping of an heiress, and it had been he who suggested that the heiress be made crazy instead of ransomed.

—Stephen King, The Stand

Patty Hearst heard the burst of Roland’s Thompson gun and bought it.

—Warren Zevon, “Roland the Thompson Gunner”

Two of the more imaginative writers of the 1970s used the Patty Hearst story to add verisimilitude to their own stories, in the process creating myths about the young woman’s perils. It is easy to see why. Her abduction and subsequent conversion to the Symbionese Liberation Army required a myth for the story to make sense, the surest sign that there are things going on that people didn’t understand. Just as some people find it helpful to create filler to link scenarios because of a lack of useful information, so do creative people use myths to make sense of a reality that is—for the moment—otherwise inexplicable.

For two years she commanded very serious media attention and abruptly the story was gone. Little has been written of her since her pardon by President Jimmy Carter. Her 1982 autobiography, Every Secret Thing, sold few copies and the Paul Schrader movie based on the book did little at the box office. Today she is scarcely recalled except as a nostalgia item or as a hostess on the Travel Channel. Yet prior to her capture, Patricia Hearst, daughter of publishing magnate Randolph A. Hearst, was granted media shine surpassed in intensity only by the O.J. Simpson affair. But where the Simpson defense raised issues of racism, Hearst’s attorneys suggested the more complex issues of coercion, intimidation and conditioning. The jurors—not to mention much of the general public—scoffed at the notion that the young rich girl had been brainwashed or even succumbed to coercion, which the Merriam Webster Dictionary of Law defines as “The use of express or implied threats of violence or reprisal or other intimidating behavior that puts a person in immediate fear of the consequences in order to compel that person to act against his will.” So important is the concept of coercion in the American legal system that it may actually be a defense in a legal proceeding if the jury accepts the defendant’s behavior as the result of duress. As one looks at the facts of the kidnapping, it is quite possible to conclude that the jury accepted Hearst’s defense, but was sufficiently predisposed against her to give the defense adequate weight. It is also possible to conclude that the notion of conditioning is unacceptable to most Americans. And it is even possible that Hearst’s version of events was a lie and that the jury was too intelligent to believe it. A final explanation is that the entire business with Charles Manson had so frightened people about “politically” motivated cults that the SLA was damned from the outset.

Certainly there are parallels between the Hearst saga and the Manson killings. Both cases involved charismatic leaders and impressionable followers. Both leaders had the stigma (or badge of honor) of being an ex-convict. Both leaders were older than their followers. Both leaders gave their followers new names and new identities. Both leaders used isolation to control their followers. Both men implied that they themselves were something more than human. Both foresaw African Americans leading a revolution. Both viewed the white establishment as the enemy and referred to that enemy as “pigs.” Both forced their associates to undergo rigorous training. Both divided their organizations into military units which ultimately caused the downfall of the leader himself. And both led groups that carried on after the imprisonment or death of their leader.

A cactus grows in the desert because it can grow nowhere else. The seeds of the behavior of the members of the SLA only came to fruition under the conditions provided by their leader.

“You do indeed know me,” Cinque said in his first taped message to Randolph Hearst. “You have always known me. I’m that nigger you have hunted and feared night and day. I’m that nigger you have killed hundreds of my people in a vain hope of finding. I’m that nigger that is no longer just hunted, robbed and murdered. I’m that nigger that hunts you now.”

A jail rat from the age of sixteen, Donald DeFreeze discovered his true self in San Quentin, where he was reborn as the Fifth Prophet: Cinque Mtume. After being transferred to Soledad Prison, Cinque became a trustee. In March 1973, he was babysitting a boiler when he felt the spirit swell up in him. Epiphanized, he leapt a fence and completed his escape. In Berkeley, he connected with friend Russ Little and soon the two men moved in with female radical Pat Soltysik (Zoya). These three formed the original core of the Symbionese Liberation Army. Little’s girlfriend Angela DeAngelis (Celina) soon joined, as did friends Joe Remiro and Willie Wolfe (Cujo).

.jpg)

William Wolfe had been a middle class social success and social worker when he met Cinque as part of a program to educate African-American prisoners. The teacher ended up receiving the education. Cujo was born.

Angela DeAngelis had likewise come from an affluent family. At college In Indiana, she and future husband Gary Atwood became fast friends with Bill and Emily Harris. Radicals were not much tolerated in Indiana, even in the late 1960s, and so the group found their way to Berkeley, as did Nancy Ling Perry (Fahizah), a former Goldwater Republican who transferred from Whittier College. She was impressed with the free love, free speech, cheap drugs and cozy camaraderie of the local radical scene and through her work in prison reform she discovered the SLA.

Camilla Hall (Gabi) also identified with society’s outcasts. The artistically gifted gay young woman met Zoya and soon moved in with her. It was through this relationship that she found acceptance in the guerrilla group.

In late 1973 Russ Little and Joe Remiro were arrested for murdering Marcus Foster, the first black superintendent of schools in Oakland and—according to the SLA—the original Uncle Tom. Field Marshall Cinque could not allow his loyal comrades to remain in captivity. An exchange was in order. But what did the SLA possess that they could trade for the release of two convicted murderers?

On Monday, February 4, 1974, three SLAmembers entered the apartment shared by Steven Weed and Patricia Hearst. The intruders beat Weed unconscious, blindfolded Hearst and brought her to their hideout where they required her to stay in a closet for almost two months, leaving the cramped quarters only for supervised bodily functions and the occasional tub bath.

Cinque knew that to immediately demand an exchange of prisoners was not only futile but self-serving, Instead, through a series of tape recorded communiqués, he insisted that the Hearst Corporation give seventy dollars worth of food to every indigent Californian. The Hearst family made a counter-offer of two million dollars earmarked for a program called People In Need. The ultimate result was a food distribution to a few thousand poor people. Governor Ronald Reagan had someone in his office instruct him to assure Californians that there would be no exchange of prisoners.

During the ongoing food distribution, Patty Hearst was subjected to the constant rhetoric of the nine SLA members who held her fate. Blindfolded for fifty-seven days and nights, she was told over and over that the Establishment, in the person of her father, was responsible for her imprisonment due to his lack of concern for the starving masses in California and even for the safety of his own daughter. All the rich people, all the people who made the rules, Cinque told her, were all just like that. Over and over she was told her Establishment family would sooner let her die than give up any of their precious money.

Was she going to be killed? asked the nineteen-year-old Patty Hearst.

Yes, it might be necessary for her to die. But even if the SLA did not kill her, the authorities surely would. The FBI was conducting house-to-house searches. Once they found the hideout, they would kill all the inhabitants and blame Patty's death on the revolutionaries.

Over and over. The programming took hold.

In one of the communiques sent to her parents, Patty is heard to say:

I no longer fear the SLA because they are not the ones who want me to die. The SLA wants to feed the people and assure safety and justice for the two men in San Quentin. I realize now that it's the FBI who wants to murder me.

Ms. Hearst later argued that she was forced to repeat the message and did not truly believe in the content.

It was shortly after the release of this message that Cinque offered to allow Patty to join his organization. With the earlier communiques, the SLA had laid the groundwork for convincing the public their hostage was on the road to conversion. Now Cinque told the heiress she could stay and join, or she could simply go home. Hearst later stated that she believed that if she had chosen to go home, she would have been murdered. And so she told the Field Marshall she wanted to join. In turn, he gave her the name Tania.

On April 15, 1974, something occurred which would become a key determinant in the way the public viewed the criminal justice system. It was on that day that the SLA robbed the Hibernia Bank in the Sunset District of San Francisco at Noriega and 22nd Avenue. The robbery was planned to provide funds to support the SLA's revolution. The robbery was also intended to let the media see Tania in the role of a committed urban guerrilla. While the bandits made off with $10,660, Patty Hearst was caught on tape holding a carbine on bank employees and customers.

On April 15, 1974, something occurred which would become a key determinant in the way the public viewed the criminal justice system. It was on that day that the SLA robbed the Hibernia Bank in the Sunset District of San Francisco at Noriega and 22nd Avenue. The robbery was planned to provide funds to support the SLA's revolution. The robbery was also intended to let the media see Tania in the role of a committed urban guerrilla. While the bandits made off with $10,660, Patty Hearst was caught on tape holding a carbine on bank employees and customers. Evelle Younger had become California's Attorney General based on his office's successful prosecution of the Manson Family back when he had been the Los Angeles District Attorney. His opinion was ominous: "The moment of truth has long since passed for Patricia Hearst."

Evelle Younger had become California's Attorney General based on his office's successful prosecution of the Manson Family back when he had been the Los Angeles District Attorney. His opinion was ominous: "The moment of truth has long since passed for Patricia Hearst."The public perception began to be formed.

In May 1974, Patty Hearst was waiting in a van outside Mel's Sporting Goods while Bill and Emily Harris went inside to shop. Bill chose to shoplift and was just leaving the store when an employee wrestled him to the ground. In response, Hearst aimed a submachine gun out the van's window and fired thirty rounds into the air. Emptying that weapon, she then fired three more shots from her own carbine. Asked by authorities to explain why she did this, she thoughtfully replied:

I acted instinctively, because I had been trained and drilled to do just that, to react to a situation without thinking, just as soldiers are trained and rilled to obey an order under fire instinctively, without questioning it. The penalty for failure in combat was death.

In the process of making their escape, the trio stole two cars and kidnapped two people who were released within a few days.

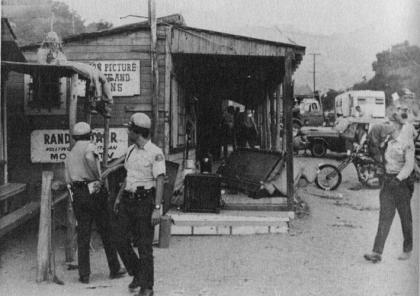

Patty and the Harrises were holed up in an Anaheim hotel when the TV news telecast the first reports: The police found the SLA safe house, fired over 3,500 shots into the building, lobbed in tear gas, and the hideout caught fire. Except for the three frightened folks watching TV in Anaheim, the entire SLA was dead.

Sportswriter Jack Scott contacted the survivors. He told them he wanted to write a sympathetic account of the SLA. Scott, his parents and his wife transported the group east where the fugitives would be somewhat less recognizable. Along with Revolutionary Army member Wendy Yoshimura, they lived in various farm houses in New York and Pennsylvania.

Sportswriter Jack Scott contacted the survivors. He told them he wanted to write a sympathetic account of the SLA. Scott, his parents and his wife transported the group east where the fugitives would be somewhat less recognizable. Along with Revolutionary Army member Wendy Yoshimura, they lived in various farm houses in New York and Pennsylvania.The group made it back to California by February 1975, settling in Sacramento with new friends Mike Bortin, Jim Kilgore, Steven Soliah and Steven's sister Kathy. Their first target was the Guild S&L Association, where they netted $3,700. Next they assaulted the Crocker National Bank in Carmichael. It was there that Emily Harris shot and killed a customer named Myrna Lee Opshal. Becoming more confident, the group turned to setting off car bombs beneath police cars. In September, the group separated. Patty and Wendy move in together in the Outer Mission District and that was exactly where the FBI arrested them, an hour after nabbing the Harrises.

Wendy Yoshimura

F. Lee Bailey and Al Johnson defended Hearst against charges of armed robbery and aggravated assault. Better than half the people surveyed in California at the time of Patty's arrest believed she had staged her own kidnapping. As Hearst herself would later ask, "How would it appear to the voters if the Ford administration, which had pardoned Richard Nixon, had chosen not to prosecute me?" Bailey and Johnson tried to persuade the jury that their client had been acting under duress, which, they explained, is the wrongful compulsion that induces a person to act against his own will. The jury was not persuaded and found her guilty of the Hibernia robbery. Originally sentenced to twenty-five years in prison, the punishment was later reduced to seven years. She subsequently was given five years probation for pleading "no contest" on the charges stemming from the Mel's Sporting Goods shoot-out. Two appeals on the Hibernia sentence were denied. On May 15, 1978, she began serving time in Pleasanton. Her sentence was commuted by President Carter and she left prison on February 1, 1979.

Perhaps the ironic aspect of the Hearst saga is that today few people read, write or concern themselves with her plight. And yet the big question remains: When a microcosmic society conspires to alter a person's thinking, what is the responsibility of that individual for their own behavior?

No comments:

Post a Comment