In 1971 a group of film students wrote, directed, produced and acted in a movie called Billy Jack. The film, which starred Tom Laughlin and Dolores Taylor, was dependent for approval first upon the pre-existing politics of the viewer and second upon that viewer's decision about the acceptable means of achieving political change. Naive and simplistic, Billy Jack was also brash, daring, and quite accurate in its message that pacifists exist at the mercy of emotional heathens. And emotional heathens have a history of being unmerciful.

Billy: You worked with King. Where is he?

Jean: Dead.

Billy: And where are Jack and Bobby Kennedy?

Jean: Dead.

Billy: Not dead. They had their brains blown out.

The significance of this movie should not be underestimated. Not many films released in the USA have suggested that the Allies lost World War II or that the government's government is none too benignly fascist or that it is not only appropriate but even urgent to defend the country against that government. The film makes the choices simple. The man v. man conflicts are (a) oppressed native Americans versus reactionary WASPs, (b) communal dwellers versus urban despot, (c) youth versus aged, (d) poor versus rich, (e) free versus neurotic, and (f) good versus evil. At the time, those who enjoyed the film saw it as an inspirational work that gave hope to those opposed to the status quo. Today, such a film would be considered inspired propaganda, even by those who agree with its central themes, just as today such once revolutionary philosophies have been co-opte and perverted by right wing separatists who find safe havens in Idaho and Montana.

1971 saw the release of another subversive film, this one a celluloid adaptation of the Anthony Burgess novel, A Clockwork Orange. Stanley Kubrick's film was just as subversive and yet even more persuasive and down right manipulative than Billy Jack. Beginning with loud synthetic dominant strands of mostly familiar classical music, the movie leads the audience into the protective hands of Alex, the protagonist and "humble narrator." Alex lives in a future where every impulse and action is ultimately and merely functional, and in the process extrapolates on the conservative uses of liberal reform, even though it is impossible to tell who are the reformers and who are the reactionaries. Alex is a truly despicable character. He leads an assault on a drunken old man, he whips other young folks with chains, he steals a car and runs people off the road with it, he cripples a writer and makes him watch while the gang of "droogs" rapes his wife. And it is this despicable Alex with whom the audience is compelled to identify. Alex is not only the voice and figure that directs the audience through the adventures of the movie; he is proudly nonmechanical and unartificial. So even though he is the embodiment of free evil, we the audience become upset when he is manipulated by a state mechanism that is certainly no nobler than young Alex. The identification with what has been improperly called an anti-hero was reinforced many ways, perhaps most cleverly as we see Alex become programmed to have unpleasant physical responses to hearing Beethoven's Ninth Symphony and slowly realize that something similar has happened to us when we hear "Singing in the Rain," a song Alex sings while leading the gang rape.

Kubrick's earlier film, 2001: A Space Odyssey, has received the most fluctuating degrees of praise and condemnation of any major mation picture. Based on the story by Arthur C. Clarke and released in 1968, 2001 was loved by dopers and art film aficionados, but the general reaction was voiced by Rock Hudson, who reportedly fled the theatre shouting, "Will somebody please tell me what this film is about?!?"

The problem with Mr. Hudson was that--as with so many others who found the film boring--he simply asked the wrong question. One might as well have responded, "Oh, it's about two hours" as to have labored on about the ascent of man and other concepts that loosely unify the manifestation of the director's realization of the senses involved in film appreciation: sight and sound. A great movie such as A Hard Day's Night is certainly not about anything either. Nevertheless, it was entertaining, life-affirming, and as with Kubrick's film of four years later, contained visual scenes and snips of dialog that tend to be retained by the audience for far longer than seems reasonable. Anyone who has watched the Richard Lester Beatles film will recall the response John Lennon gives the interviewer who asks how he found the United States. "Turned left at Greenland." Anyone who has watched the Kubrick film will remember the astronaut's command to the space system computer: "Open the pod door, HAL." This act of instilling memories is nothing short of classical conditioning.

Kubrick has accomplished the conditioning miracle in two other films: The Shining and Full Metal Jacket.

The Shining, before it was a movie, was a novel. The man who wrote the novel was Stephen King. At that time, 1978, Stephen King's books were of the horror genre. The Shining was so intensely horrifying that it was at times psychologically painful, higher praise for which does not exist. By contrast, the movie was not painful. The movie lured the viewer in most seductively, went together waltzing, cleverly cascading through unexplained episodes that again were too compelling not to be trusted.

The King people hated it. Adherents of strict translation of novel to film felt betrayed, generic horror fans shrugged out of the theatre (no doubt thinking, "Will somebody please tell me what this film is about?!?"), and King himself was so displeased (he claimed that among other things, he strongly disliked Jack Nicholson's performance and felt this was very much the wrong actor because his work in an earlier film, One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, led people to assume the same character had stumbled into this film) that twenty years later he produced the abysmal remake entitled Stephen King's The Shining.

Despite the objections of literary purists, the Kubrick film was not only cinematically magnificent, it also pulled off associations and manipulations equally affecting casual viewer and celluloid scholars. the perfect mental association is formed when the Jack Torrance character (played with superhuman strength by Nicholson) destroys the bathroom door behind which his wife and son are hiding, puts his face up to the curtain of wood, and prefatory to the anticipated slaughter of his family, bellows with great jocularity, "Here's Johnny!" So successful was that burst of tension relief and so exact was the actor's delivery that from that moment on it became impossible to listen to Ed McMahon's introduction for his boss on "The Tonight Show" without conjuring up that same mental image. Earlier in the same motion picture, the audience is persuaded to identify with Jack Torrance, even though this character becomes a very bad man. His wife, Wendy, played by Shelly Duvall, does not deserve the bad things that her husband is trying to do to her. And yet the audience is clearly pulling for Jack. In one familiar scene, Wendy is protecting herself from Jack by wielding a baseball bat. Jack has the funny lines, the motivation, the flattering shots, and far more name and visual recognition than Ms. Duvall, who in her character comes across weak, helpless, and pathetic. It may be that Kubrick lured the audience into siding with Jack because the director believed that we could only understand the character's public and private demons if we sympathetically identified with that character. Or, just as likely, the director himself enjoyed this type of psychological manipulation and may even have felt his film's successes depended upon this.

Whatever Kubrick's motives, his unparalleled skill in group coercion made it perfect that he would direct one of the best films about the Vietnam War, Full Metal Jacket.

By the late 1970s, the war experience had become fodder for movie studios. The very fact of a film being made about the war suggested the slant would be anti, but that was not necessarily so. Coming Home, starring Jane Fonda, Bruce Dern and Jon Voight, was certainly a film that did not seem to much care for the war in as much as Voight--whose character was crippled--was able to "give" Fonda the orgasm her pro-military husband Dern could not. But besides that and a great period piece soundtrack, the movie offered little. Not much better was The Deer Hunter, although it did deal with the psychological horrors affecting people long after the war was over. And even though Oliver Stone would later make two excellent films was the war as the focus, for the better part of a decade, Francis Ford Copolla's Apocalypse Now was the ultimate Vietnam War film.

And for very good reason. Based tangentially on the Joseph Conrad short novel Heart of Darkness, Apocalypse Now, in the words of its director, "wasn't about Vietnam. It was Vietnam." True enough. This was a big film with big actors and a big budget and there can be no doubt that anyone who has seen the movie has come away with at least snippets of realization of what the war was like. Copolla's intent was not to sermonize or persuade, and the film is genius in the way it deals with power without dealing with politics. The audience finds darkness, they find madness, but they are finding it less through their own eyes than through those of Willard, the captain played by Martin Sheen.

And that is not something which can be said about Full Metal Jacket. FMJ used a creative reportage journey style of telling its story, but where Apocalypse Now moved slow and inexorably closer to the darkness of Kurtz, Kubrick's film was calculated second by second. Comprised of three parts, the movie begins with the post-induction pre-boot camp scene where the inductees have their long hair clipped off to the tune of Tom T. Hall's "Hello Vietnam." Young male volunteers, dozens of them, one after another, are freed from the liberation of their hair. The second part of the film is boot camp itself, where the audience is in the hands of Private Joker, our humble narrator. the Private has written "Born to Kill" on his helmet and wears a peace button on his uniform, which, he explains, is an attempt to say something about the duality of man. Kubrick brings back the Orange-style coercion as we watch a fat, stupid, frustrating recruit played by Vincent D'Onofrio be brutalized by his squad one night in retribution for a punishment doled out by the drill instructor. Since few in the audience desire to identify with an overweight ignoramus, the lure is to side with the group against him. But since Joker is the protagonist, we wait to see what he will do. He does exactly what an eighteen-year-old Marine would do under those conditions and administers a particularly savage beating. The ethics being thus resolved, the audience is freed to savor the brutality.

The final part of the film is set during the Tet Offensive, where our Marines are in Vietnam, fighting it out in an infantry gang where it quite appropriately becomes a challenge telling good guy from bad. But Kubrick doesn't so much play fair as he plays real. Having already accepted so much brutality upon the person of Joker, and having already rationalized that Joker's antisocial behavior was acceptable, the slaughter of the Vietnamese in turn may become an alright thing as well, just as it did in real life.

Aside from the fact that this is precisely how societal evils become palatable to the majority of media-hungry processing units, the prime message of all these Kubrick films is sobering: if the public can be manipulated, can be aware of the manipulation, and in spite of that fact continue to respond to the manipulation, then is it not just as likely that the audience is being conditioned outside the movie theatre and may even be acting complicit and in concert with that far more significant level of manipulation?

The key element in any act of manipulation or coercion is the perceived authority of those in a presumed position of power over those potentially being controlled. In 1962 and 1963, psychologist Stanley Milgram conducted a series of experiments at Yale University devised to test obedience. Forty participants were told they were engaging in an exercise to measure the effects of aversion on memory. The participants were told to read a series of questions and answers via intercom to subjects behind a separating wall. After this, the participants were to ask the questions again, and this time the learners would attempt to give the correct answer. If the learner gave the wrong answer or failed to reply, the teachers were to administer increasingly higher levels of punitive electric shock. Aversion treatment apparently played no role in memory retention because the learners begged and pleaded for the horribly painful shocks to stop. Despite the fact that the learners argued and shouted that they had heart conditions, and despite the fact that ominous silence eventually became the learners' response, sixty-five percent of the teachers followed Milgram's orders to administer the highest voltage possible, a level several steps beyond which the learners pounded on the wall and begged for release. Several teachers became emotionally disturbed as a result of what they realized about themselves in this and subsequent experiments, even after it turned out that the learners were simply acting and were not actually being shocked. As Dr. Milgram described it: "With numbing regularity, good people were seen to knuckle under to the demands of authority and perform actions that were callous and severe. Men who are in everyday life responsible and decent were seduced by the trappings of authority, by the control of their perceptions, and by the uncritical acceptance of the experimenter's definition of the situation, into performing harsh acts. A substantial proportion of people do what they are told to do, irrespective of the content of the act and without limitations of conscience, so long as they perceive that the command comes from a legitimate authority."

Milgram came under substantial criticism for his experiments, mainly because they tended to reveal unsettling things about how people are so easily able to exert power over willing "victims." After all, if we knew that the power came from us, we might choose to withhold it. Fed up with distracting questions about his ethics, Milgram replied:

I started with the belief that every person who came to the laboratory was free to accept or to reject the dictates of authority. This view sustains a conception of human dignity insofar as it sees in each man a capacity for choosing his own behavior. And as it turned out, many subjects did, indeed, choose to reject the experimenter's commands, providing a powerful affirmation of human ideals.

Milgram was pleased that not everyone went to the final level. He describes one such encounter.

The subject, Gretchen Brandt, is an attractive thirty-one-year-old medical technician who works at the Yale Medical School. She had emigrated from Germany five years before. On several occasions when the learner complains, she turns to the experimenter cooly and inquires, "Shall I continue?" She promptly returns to her task when the experimenter asks her to do so. At the administration of 210 volts she turns to the experimenter, remarking firmly, "Well, I'm sorry. I don't think we should continue."

Experimenter: The experiment requires that you go on until he has learned all the word pairs correctly.

Brandt: He has a heart condition. I'm sorry. He told you that before.

Experimenter: The shocks may be painful but they're not dangerous.

Brandt: Well, I'm sorry. I think when shocks continue like this they are dangerous. You ask him if he wants to get out. It's his free will.

Experimenter: It is absolutely essential that we continue.

Brandt: I'd like you to ask him. We came here of our free will. If he wants to continue I'll go ahead. He told you he had a heart condition. I'm sorry. I don't want to be responsible for anything happening to him. I wouldn't like it for me either.

Experimenter: You have no other choice.

Brandt: I think we are here on our own free will. I don't want to be responsible if anything happens to him. Please understand that.

She refuses to go further. And the experiment is terminated. The woman's straightforward, courteous behavior in the experiment, lack of tension, and total control of her own action seem to make disobedience a simple and rational deed. Her behavior is the very embodiment of what I envisioned would be true for almost all subjects.

Unfortunately, most of the time, what Milgram encountered was the horrifying scenario recounted below.

Fred Prozi's reaction, if more dramatic than most, illuminate the conflicts experienced by others in less visible form. About fifty years old and unemployed at the time of the experiment, he had a good-natured, if slightly dissolute, appearance, and he strikes people as a rather ordinary fellow. He begins the session calmly but becomes tense as it proceeds. After delivering the 180-volt shock, he pivots around in the chair and, shaking his head, addresses the experimenter in agitated tones:

Prozi: I can't stand it. I'm not going to kill that man in there. You hear him hollering?

Experimenter: As I told you before, the shocks may be painful, but. . .

Prozi: But he's hollering. He can't stand it. What's going to happen to him?

Experimenter: The experiment requires that you continue, Teacher.

Prozi: Aah, but, unh, I'm not going to get that man sick in there. Know what I mean?

Experimenter: Whether the learner likes it or not, we must go on, through all the word pairs.

Prozi: I refuse to take the responsibility. He's in there hollering.

Experimenter: It's absolutely essential that you continue, Prozi.

Prozi: There's too many left here. I mean, Jeez, if he gets them wrong, there's too many of them left. mean, who's going to take the responsibility if anything happens to that gentleman?

Experimenter: I'm responsible for anything that happens to him. Continue, please.

Prozi: All right. The next one's "Slow--walk, truck, dance, music." Answer please. Wrong. A hundred and ninety-five volts. "Dance."

Learner: Let me out of here! My heart's bothering me!

Experimenter: We must continue. Go on, please.

Prozi: You mean keep giving him that? Four hundred fifty volts, what's he got now?

Experimenter: That's correct. Continue. The next word is "white."

Prozi: "White--cloud, horse, rock, house." Answer, please. The answer is "horse." Four hundred and fifty volts. Next words, "Bag--paint, music, clown, girl." The next answer is "paint." Four hundred and fifty volts. Next word--

Experimenter: Excuse me, Teacher. We'll have to discontinue the experiment.

If filmmaker Stanley Kubrick was unaware of Milgram's test on obedience, he apparently drew the same conclusions. People can be controlled in a democracy as long as they bestow authority or responsibility upon the person directing their behavior. For a film director such as Kubrick, his repudiation alone is nearly enough to persuade an audience to obey. Add to that the celebrity of his actors, the magnificence of his craft, along with the dark black confines of a movie theatre, and one has sufficient conspiring elements to twist the moviegoer's ear in favor of endowing the director with unconditional power.

Such cinematic exercises have been trivialized since the 1980s. Now audience manipulation is unsubtle and direct in ways that would have embarrassed the makers of Billy Jack. In a film such as Speed, for example, the good guys and bad guys are grossly two-dimensional, the plot is action, the conflict is mechanical, character development is inherent in the good or bad looks of the character, and whatever minimal audience manipulation does exist can only be measured in a reduction of alpha waves.

A few noteworthy and refreshing exceptions to this trivialization do exist. In 1991, Oliver Stone released JFK. Stone is possibly the only big money filmmaker working in America today who can approximate the Kubrick-style conditioning, and JFK proves the point. Predictably, the movie was bludgeoned by much of the media and was attacked by American intellectuals and nincompoops alike for the agreed-upon charge of distorting history.

Stone argued that some of his attackers had a vested interest in maintaining the myth of the Warren eport. That may well be true, but no one would have cared at all what the film was saying had it not been said with such authority. In the context of the film, the theory that forces within the U.S. Government conspired to kill John Kennedy because he supposedly deserted the cause of anti-Castro Cubans and was signaling an end to U.S. involvement in Vietnam is a sharply convincing one. JFK is a motion picture that leads the viewer to consider his or her own programming while being programmed to do so. Or, as Stone himself said, "It is a counter myth." Or, as Kevin Costner, in the role of prosecutor Jim Garrison, says in his closing remarks to the jury:

I believe we have reached a time in our country, similar to what life must've been like under Hitler in the 1930s, except we don't realize it because fascism in our country takes the benign disguise of liberal democracy. There won't be such familiar signs as swastikas. We won't build Dachaus and Auschwitzes. We're not going to wake up one morning and suddenly find ourselves in gray uniforms goose-stepping off to work. "Fascism will come," Huey Long once said, "in the name of anti-fascism." It will come with the mass media manipulating a clever concentration camp of the mind. The super state will make you believe you are living in the best of all possible worlds, and in order to do so will rewrite history as it sees fit.

It is not always a simple matter to determine what constitutes a political film. Is it more political to challenge authority than to support it? Is a political film one that strives to unearth some secreted fundamental facts about the nature of society, or is it one that champions the individual psychology as true political enlightenment? Or is a political film only one that is about politics or politicians?

The problem with such questions lies in assuming that a movie can only be political, as opposed to being romantic, thrilling, action-packed, or comedic. The fact is that hundreds of major motion pictures have been made that had very strong political messages, or that at least were weighted with political connotations.

Hundreds of major motion pictures have been made that have had strong political messages, or that were weighted with political connotations. Some of the more familiar ones are On the Waterfront, Patton, Silkwood, The China Syndrome, The Candidate, All the President's Men, American Beauty, Natural Born Killers, Nixon, Salvador, Platoon, Wall Street, Born on the Fourth of July, Network, An American President, Primary Colors, Red Dawn, Rambo, and Top Gun. Lots of other films could have been on this list. These, however, will do well to explicate the different visions filmmakers can convey when creating movies whose meanings go beyond psychotic car chases and unconventional love stories.

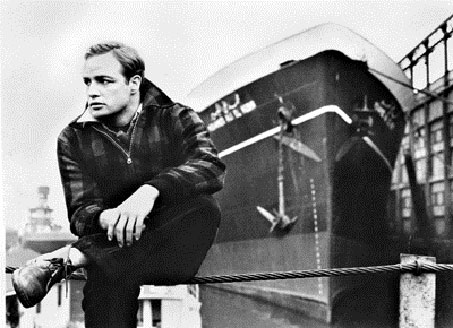

On the Waterfront wastes no time announcing that it is not merely a love story, unconventional or otherwise.

Elia Kazan |

A political film does not require a mono-dimensional story-line and can in fact have multiple subtexts occurring simultaneously. To that end, On the Waterfront becomes even more political in the fact that it addresses moral choices of genuine consequence that may have something incidental to do with boy-girl love, but more importantly have to do with social responsibility. It is also a political movie in that it not so much suggests as insists that there is propriety in selling out friends for the greater good. Naturally, the movie does not even hint that people who have sold out their friends tend to heavily amplify just what that greater good is. Elia Kazan, the director whose name is synonymous with this film, did sell out his friends when he testified to the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) about his associates in the motion picture industry who might have been communists. Such allegations resulted in those writers, actors and directors being blacklisted by the movie studios, meaning that because of alleged or real political affiliation, Americans in the entertainment industry could not get work. And so the film takes on an interesting irony not lost on Victor Navasky, in Naming Names:

A story is told that in 1955, after Arthur Miller had finished A View From the Bridge, his one-act play about a Silcilian waterfront worker who in a jealous rage informs on his illegal immigrant nephew, Miller sent a copy to Elia Kazan, who had broken with him over the issue of naming names before HUAC. "I have read your play and would be honored to direct it," Kazan is supposed to have wired back. "You don't understand," Miller replied. "I didn't send it to you because I wanted you to direct it. I sent it to you because I wanted you to know what I think of stool pigeons." They had planned to collaborate on a movie about the waterfront called "the Hook," but now Kazan went on to do his own waterfront picture, On the Waterfront, in which Terry Malloy comes to maturity when he realizes his obligation to fink on his fellow hoods. And Miller wrote View, which tried simultaneously to understand and condemn the informer. Kazan emerged in the folklore of the Left as the quintessential informer, and Miller was hailed as the risk-taking conscience of the times.

In its annual celebration of itself, in 1999 the Motion Picture Academy chose to honor Kazan with a lifetime achievement award, albeit, a posthumous one. The movement to honor Kazan was led by National Rifle Association chairman Charleton Heston. Many of those in attendance sat on their hands rather than applaud Heston's attempt to commemorate Kazan.

In 1970, the reactionary icon at the box office was a dead man. The movie of his life, Patton, was brilliant. Aside from its masterfully artistic pseudo-docudrama stylings, the film was hugely popular among critics and general public alike in large part because actor George C. Scott, as the title character, General George S. Patton, dwarfed the flag in front of which he paraded. The film was an artistic success in even larger part because Scott's portrayal was so extreme that the Left could misinterpret the film as a potently wicked satire while the Right could consider it a validation of their own deepest desires.

The character of general Patton and the makers of the two nuclear power films on our list looked at the world in different ways. The motion picture about Karen Silkwood, an actual worker at an actual nuclear reactor plant who herself was contaminated by radiation, was important, if not altogether timely. Brave in many respects, the title character of Silkwood, played by Meryl Streep, was a warts-and-all performance that involved drinking, swearing and smoking, as well as a hint at a lesbian relationship and an aversion to unstable reactor maintenance. The verisimilitude of Silkwood's persona was well handled. The difficulty some critical viewers had with the film was in the destruction of the real life protagonist. In the film, Karen Silkwood is murdered by as-yet unnamed assailants. (The film, however well-acted, was directed by the estimable Mike Nichols, whose fondness for the touch of the hand that feeds him is so strong he doesn't bite it; he gums it. There really isn't much indication of foul play in the film, at least not not indication to rock the system Nichols only pretends to distrust. As a postscript to the story, I quote here from the remarkably pro-system PBS Online: "The saga of Karen Silkwood continued for years after her death. Her estate filed a civil suit against Kerr-McGee for alleged inadequate health and safety programs that led to Silkwood's exposure. The first trial ended in 1979, with the jury awarding the estate of Silkwood $10.5 million for personal injury and punitive damages. This was reversed later by the Federal Court of Appeals, Denver, Colorado, which awarded $5,000 for the personal property she lost during the clean-up of her apartment. In 1986, twelve years after Silkwood's death, the suit was headed for retrial when it was finally settled out of court for $1.3 million. The Kerr-McGee nuclear fuel plants closed in 1975.") The movie quite logically leads the viewer to suspect that forces within the nuclear industry arranged for this to happen. What was not suggested by the filmmaker was a far more sinister shadow over the tragic business, one which Mark Lane intimates in Plausible Denial:

David Burnham had covered nuclear energy stories for the New York Times. Karen Silkwood, knowing of his specialty, had arranged a secret meeting with him to deliver documents to the Times. almost no one knew of the planned trip save Silkwood and Burnham. She never met him; she was apparently murdered on the way to see him and her documents disappeared.

Somewhat less interesting was The China Syndrome, a film that had going for it only Jane Fonda and Jack Lemmon, along with a release that coincided with the accident at Three Mile Island in which poisonous gases were released into the skies of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. (The John Birch Society found this to be more than coincidence, strongly implying that Fonda had arranged for the accident to happen in order to boost ticket sales, quite a feat for a Hollywood starlet.) Lemmon was the real star, playing a man caught between the desire to be a loyal employee and an urge to prevent a reactor core to melt through to the water table, thereby creating a toxic geyser. The facts are painted clearly and the science is made disturbingly understandable, all the actors are comfortable in their roles, and the story works. There are realistic bits where plant workers wonder how Jane will get the power to operate her blow dryer and the reporters run into the normal diabolic resistance from PR flacks, as well as from freaks within the news organization. But somehow one simply does not quite get the idea that this could be the end of the world, at least when taken out of the historic context of President Carter inspecting Three Mile Island in ridiculously bright yellow boots.

However uneasy Carter may have appeared throughout most of his Presidency, it paled to Robert Redford's character in The Candidate. Redford joined with director Michael Ritchie to form a production team. In 1972 they released one of the most intricately fascinating motion pictures of all time. Redford stars as a Jerry Brown-style man of the beautiful people, one who is pro ecology, pro choice, and pro small labor. He even has a father who held the political power in the state of California (a la Pat Brown). The screenplay was written by Jeremy Larner, a talented writer who had created speeches for Eugene McCarthy four years earlier, witnessing first hand how the business of getting elected is a real business. But this is not just another take on the selling of the president. Where Larner's screenplay earned the Academy Award that it won and where Redford's talents as an actor truly sparkle are in the depiction of the candidate Bill McKay, struggling to be one with the people. On the one hand he cares so much about social justice that he rebels against his staff for coaching him on an up-and-coming press conference. On the other hand, when he initially mingles with workers, students, and urban dwellers, he appears vastly uncomfortable shaking hands, making eye contact and even commanding attention. Like Carter, like Brown, and like McCarthy, what Bill McKay does best is in expressing himself on issues about which he cares. It is easy to consider The Candidate as a product of the times, what with all the major progressive politicians in America neutralized either by murder or by condescension. In fact the film remains highly instructive and is in many ways a much better "Clinton movie" than any of those more closely related to the 42nd commander in chief's presidency.

Far more vulnerable and equally strong was All the President's Men. Can a movie that relies as much as this one does on public knowledge of the web-like complexities of Watergate, and of Watergate's role in sculpting the political future of the United States--can such a movie be successful decades later?

It can. Just as Casablanca, Key Largo, and Notorious--to site three easy examples--maintain their integrity despite blurred memories or historic ignorance or indifference, so does All the President's Men rise above the fascination of its subject matter to tell a great story well.

Who is in charge? |

The movie is tightly based on the book of the same name by Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward, two Washington Post reporters who investigated the break-in at the Democratic National Committee headquarters with a tenacity that would exhaust and mystify any mainstream journalist working today--journalism today often involving the decision-making process regarding which press releases to run. As presented in All the President's Men, the investigation is a detective story of unfathomable consequence. If anything, director Alan Pakula and screenwriter William Goldman go farther than the book in asserting that Watergate was just one action in the overall operation to keep Richard Nixon in the White House. What the film does not and could not address was the interesting question of why the Post and Woodward in particular were so interested in following the story even beyond Nixon's resignation when almost no other paper in the country thought the matter all that important. What was ignored--what had to be ignored--was the question of whether the Post was being used as a CIA media asset to destroy Nixon as part of a limited hang out whereby the Agency admits to a certain amount of illegal activities to divert attention from larger issues, or, more likely, to rid the Agency of Nixon, who was taking serious action to control the CIA. Even though the film pulls back from these questions, it still manages to be one of the most enlightening and entertaining political films of all time.

Who is in charge? |

Another magnificent political motion picture is American Beauty, a film discussed months ago in this blog but one which deserves our attention here for other reasons. The recurring message of this splendid film is to "look closer," and indeed--politics aside--looking closer is what this movie is all about. American Beauty at first seems to be a story of Lester and Carolyn Burnham and the power shift to destruction their marriage becomes. If that were all there were to this movie, cinematographer Conrad Hall would still have mined a gem. But upon renewed viewings, Annette Benning as Carolyn shows that she is passionately determined to castrate men over who she has gained sexual control, which is why she gets along so well with the homosexuals next door; that Kevin Spacey as Lester achieves some measure of triumph by regressing to the attitude of a teenager who is rebelling against his mother rather than against his wife. Looking closer we see that the political symbol underneath a neighbor's dinner plate represents the underside of culture, so perfect and so corrupt; that much of the self-help merchandise available is a way for people to quite literally program themselves to do stupid things; and that roses are often use to disguise monumental ugliness. There are so many layers to this film that it may indeed be impossible to perceive them all. But where this Sam Mendes picture bears its political stripes is in tying all the scenes together into a statement of purpose: as long as we can remain clear-headed about right and wrong and act accordingly in terms of ourselves and of others, then we have found what we thought we were seeking.

Who is in charge? |

A film such as American Beauty would have been difficult to conceive during the Reagan-Bush administrations. Those twelve years of artistic repression lent themselves to high tech machismo and militarism in movies such as Red Dawn, where an attack by the Russians is defended by a rough and ready high school, or Rambo, where Sylvester Stallone grunts his way back into Vietnam to even up the score. Even so-called comedies such as Private Benjamin and Stripes were essentially recruiting films, suggesting there was still room for individual expression in the armed forces.

Who is in charge? |

But the leader of all movies in the glorification of peacetime warring was Top Gun. More an extended music video than an actual motion picture, Top Gun starred Tom Cruise and Val Kilmer, two prime poster boys for 1980's reckless ambition. Pepsi, fast cars, faster planes, and two people in love with each other for no discernible reason: all this was sprinkled amidst high technology aerial shots and power pop music about as exciting as dry ice. Admittedly a lot of good films have been based on thinner premises than this one. But the cross-marketing of soda products along with the unceasing media chatter about how thrilling the film was gave blessings to a pro-military regime.

Who is in charge? |

We've got new idols for the screen today

Although they make a lot of noises

They've got nothing to say.

I try to look amazed but it's an act.

The movie might be new

But it's the same soundtrack.

--Graham Parker, "Passion is No Ordinary Word"

Primary Colors and An American President were moderately pleasant and inoffensive pictures to varying degrees based upon or inspired by the Clinton presidency. The former focuses on the election process as seen through the eyes of a James Carville type character. The latter is a more sensitive approach to the presumed scandal that would occur should a single president have a girlfriend opt to spend the night in the White House, particularly is she happened to be the head of a large environmental concern lobbying for issues over which the President had some authority. Neither film offered any new insight into the political process or into the way power works in the United States or anywhere else. It would, nevertheless, have been hilarious if, in the latter film, President Michael Douglas had gone on TV and announced that financial contributions would no longer be an acceptable way of wielding influence in Washington. From this point forward, Douglas should have said, the bedroom is where these decisions are being made.

Who is in charge? |

Paddy Chayefsky's screenplay of Sidney Lumet's Network, however, is all about power. And while certain references (Angela Davis, the SLA, Archie Bunker) may be unfamiliar to younger viewers, the fact remains that every major and minor ideological assertion offered by this film has not only come to pass, they have become business as usual.

Who is in charge? |

The nightly news anchor of a national network, Howard Beale, learns that he is being dismissed from his twenty-odd year job because of low ratings. He responds by announcing on the next telecast that since his job is his life, he will blow his brains out on the air in one week. The network, which is in the early throes of being bought by a multinational corporation, decides Howard is onto something and they decide to keep him on the air. But instead of killing himself, Howard becomes the mad prophet of the air waves, encouraging his viewers to throw open their windows and shout, "I'm mad as hell and I'm not going to take it anymore!" The purity and humanity of Beale's pronouncements (a personal favorite: "I haven't got any bullshit left. I ran out, you see."), as well as his clarity in expressing mass angst, are the popular elements of Beale's nightly pontifications. Meanwhile, Robert Duvall and Faye Dunaway have turned the news department into a for-profit enterprise, a situation relatively unheard of in the late 1970s but commonplace ten years later and universal today. In any event, Duvall and Dunaway add all sorts of hokey malarkey to the news line-up and develop "real life" shows which they manipulate. Just as the thrill wears off, Howard Beale learns of the takeover of the network and warns the audience that bad times are coming, as is inevitable when for-profit organizations control the news.

Who is in charge? |

The head of the multinational, a brief role played to brilliance by Ned Beatty, has Howard in for a little chat. During those few minutes, Beatty verbalizes the organic nature or world domination, pointing out that the real countries of the world are ATT, ITT, IBM, Banl of America, and so on. This revelation inspires Howard to go back to his audience and assure them that everything will be alright after all. Once the viewers are reassured, they stop tuning in. So Dunaway and Duvall terminate, as it were, Beale's contract.

The total control of public airwaves by a formidable group of administrators is frightening indeed. But of course the merging of news and entertainment has already been completed and the result is strict control even over the palest slop heaped upon the viewing public, from MTV to Nick at Nite, both of which are owned by the same corporation.

It is this level of control over public information that brings us--at last!--back to 1963 and to the murder of Lee Harvey Oswald.

Because John Kennedy was assassinated while still in his first term as President, it is only possible to speculate on most elements of how the future would have differed had he lived. His National Security Action memo directives 55 and 263, as well as remarks he made to confidants, strongly suggest a reversal in Southeast Asian policy concomitant with a firmer grip on U.S. intelligence operations. Two key points, however, are quite clear. First, with Kennedy alive, Lyndon Johnson would not have appeared before Congress as he did in August 1964, demanding the enactment of the Gulf on Tonkin Resolution. Johnson, it may be recalled, made his appearance following the allegedly unprovoked attacks by North Vietnamese torpedo boats on two U.S. destroyers in the Gulf of Tonkin, attacks which thirty years later the State Department admitted never actually happened. The Resolution, unconstitutional as it was, gave the President--rather than Congress, as the Constitution requires--the authority to take all necessary measures to repel any armed attack against the forces of the United States and to prevent further aggression, and it declared the maintenance of international peace and security in Southeast Asia to be vital to American interests as well as to world peace. This law, which explicitly gave the President unlimited authority to wage total war, was not repealed until 1970. And even its reversal has not stopped certain Presidents from pretending it is still in place--Presidents such as Ford, Carter, Reagan, Bush, Clinton, Bush Jr., and Obama.

Second, had Kennedy been allowed to live, J. Edgar Hoover would have been removed as Director of the FBI, allowing the Bureau to devote more work hours pursuing criminal behavior and less to persecuting supposed subverters and seditionists such as Martin Luther King. The civil rights leader was himself assassinated April 4, 1968, suffering the same fate as Medgar Evers, Emmett Till and Malcolm X, leaving the civil rights movement with no central leadership or example. And so instead of being dead, today Reverend King might be bouncing his great grandchildren on his knees, looking back upon happier times.

Emmett Till after the gun shot blast |

But these two things did not happen. And as interesting as such speculation may be, the televised execution of Lee Harvey Oswald by Jack Ruby, two days after Kennedy's murder, had an everlasting impact upon the collective psychology of the people of the United States, certainly no less of an impact than the killing of the President. If one can imagine the public response today if the current President were to be shot and killed by a purported lone gunman who himself was executed while in police custody by a lone vigilante right on international television a mere two days later, then one begins to gain a glimpse of the suspicious cover story that was perpetrated.

Initially, Jack Ruby explained that he had murdered Lee Oswald so as to spare the widow Kennedy the ordeal of testifying at the trial of the man accused of committing her husband's murder. Months later, Ruby told Warren Commission Chairman and Supreme Court Chief Justice Earl Warren that he had information that would clear up many mysteries of the assassination. Ruby begged to be taken to Washington so that he could testify. Warren declined the invitation. Ruby died in prison a short time later. Yet even without Ruby's revelations, the very fact of his murdering Oswald shocked the nation in ways the death of the President did not. Oswald's assassination made people wonder if he had been silenced to prevent details of a conspiracy from being loosed upon the land. With Oswald alive, the odds of a lone nut versus a conspiracy were even money. But with Oswald murdered, the perceived likelihood of conspiracy soared and loomed.

The murder of Lee Oswald was real in ways the murder of President Kennedy was not. Kennedy's murder had been filmed by several different people, but it would be years before the American public would see it. Oswald's execution was televised live. And that made it real.

One second away |

Even before he was executed, stories about Oswald had emerged. The simplest of these was that he was an ex-Marine who had defected to the Soviet Union, returned disillusioned to America, drifted to a job at the Texas School Book Depository, looked out a window, saw a President going by, and shot him dead.

Decades later, piece by piece, the "reality" has changed. It is more widely understood today, thanks to the efforts of researchers such as Mark Lane, Sylvia Meager, Penn Jones, Jim Garrison, William Turner and many others, that Oswald's trip to the Soviet Union was part of an ongoing intelligence operation concocted by the Special Operations division of the Central Intelligence Agency. From the day Oswald departed for the USSR until the day he was killed in Dallas, Oswald was and remained an agent and had quite probably tried to prevent the assassination of the President of the United States.

A crisis in confidence began the moment Oswald was gunned down. The new President, Lyndon Johnson, understood that his ability to hold authority lay in his skill in restoring public faith in pluralistic democracy. His response was to form and appoint the Warren Commission.

One minute away |

Few documents have been the object of such scrutiny, derision and ridicule. Assassination researchers and Commission critics have spoken with varying degrees of eloquence against the validity of the Commission's conclusions. Pathologist Cyril Wecht summed up the mood of the critics when he suggested that the 26-volume report be moved to the fiction section of the world's libraries.

Had Oswald lived to testify (or even confess, or name names), much of the cynicism and apathy regarding American institutions might not exist today. Jack Ruby's act of violence pushed the American public closer to an emotional and intellectual numbing that it was all too ready to embrace.

One shining example of this comfortably numb state of affairs was the initial national reaction to Oliver Stone's film Natural Born Killers. Everyone in the movie is feeding like vampires on cheap thrills. No one is safe from the stupefaction of the media: kids, parents, cops, bystanders, and the two killers themselves, Mickey and Mallory Knox, played by Woody Harrelson and Juliette Lewis. By the end of the film, as the celebrated killers prepare to destroy the Australian version of Geraldo Rivera (played by Morton Downey Jr), the audience becomes unpleasantly aware of being manipulated by the media and accepts the on-screen murder as right and appropriate, as does the Wayne Gale character himself. A lot of people walked out on this movie. Some people went to see the movie for the expressed purpose of walking out on it, certainly a new twist on conspicuous consumption. Having been conditioned to reject any kind of media stimulation that involves no gratuitous violence (meaning any kind that offers horror and revulsion on a scale that screams that anyone is presently capable of such atrocities), many audience members rebelled at being lured into consciously examining the ways in which they are being conditioned. A horse will only nudge an electric fence once or twice before accepting that there are boundaries to its freedom. It is doubtful that anyone who did stay for the duration of Natural Born Killers has forgotten the experience, just as the Zapruder film of the Kennedy slaying has staying power, as does Oswald's execution. It is disturbing to consider that anyone might find these things entertaining, although Stone's film suggests that this is just so. The movie might make one wonder about the passions of others in the audience.

Since the end of World War II, and especially since November 1963, when Kennedy and Oswald were murdered, Americans have been deluged with cases of misconduct, law-breaking, and pure evil on the part of people upon whom they have bestowed authority. Complaints to one another are merely public icebreakers and jokes have become cynical sarcasm. Without the summit of salvation (or truth) in sight, faith in one's own people to overcome the barriers becomes a soft platitude. With the murder of Lee Oswald, the mountains began stacking one upon another, and the summit became a long way from home. Aspiring politicos who bray about the need for leadership keenly appreciate this condition. Genuine leadership means battling the armies of cynicism and destroying the weapons of faithlessness. Anyone elected to national public office who behaved as such a leader would inspire his or her own probably demise. Mobilizing people to believe in real democracy endangers the infant orality so painstakingly instilled and installed by those who benefit the most from the cynicism.

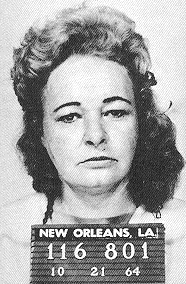

Having, I presume, established the killing of Oswald as an event of considerable significance, it may be useful now to examine how such a thing could happen. That examination will involve looking into the life of Oswald's assailant.

Jacob Rubenstein was born in Chicago in 1911. As the fifth of eight children in a tumultuous home, young Jack was extracted from his domicile and placed in various foster homes by the Jewish Home Finding Society. By the time puberty came surging along, Jack was scalping tickets, pushing posies, and selling illegal music sheets to survive. Rubenstein gravitated toward street gangs and by his late twenties was warring against the German-American Bund, an American Nazi organization. Leaving the Army Air Force in 1946, he went into sales with his three brothers. The boys thought their moniker might be holding back their success, so they shortened the last name to Ruby. The following year Jack moved to Texas to operate a nightclub.

Between the time he moved to Dallas and the day he was arrested for killing Oswald, Ruby had developed some curious friendships with local and national mobsters and with some people who would come to be known as anti-Castro Cubans. Students of organized crime and Cuban affairs may recognize the names Bernard Barker, Joseph Campisi, Frank Caracci, Frank Chavez, Josepg Civello, Mickey Cohen, Russell matthews, Chilly McWillie, Nofio Pecora, and Frank Sturgis. During those sixteen years, Ruby was arrested nine times and only convicted once, the single blot on his otherwise pristine record being for ignoring a traffic summons.

Charles "Hitman" Harrelson. Yeah, Woody's father. |

Meanwhile, Fidel Castro was winning a revolution against Fulgencio Batista. Miami crime lord Santos Trafficante and his associates were supplying guns to both sides, knowing for certain they would have backed a winner.

The United States, in the early days of the revolution, was eagerly awaiting castro's victory. Batista had become unmanagble and both the FBI and CIA supported his overthrow. One of Ruby's friends, Frank Sturgis, was acting as a close adviser to Castro while running guns and serving as a contract agent for the CIA under the name of Frank Fiorini. Sturgis later plotted to murder Castro, was involved in the bay of Pigs, is alleged by Martina Lorenz to have taken part in JFK's assassination, and was arrested as a Watergate burglar. In any event, it was through relationships with men such as Sturgis that Ruby helped the Mafia help Castro while also helping the FBI keep tabs on the mob. According to a 1964 memo FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover sent to the Warren Commission, his G-men contacted Ruby eight times in 1959, "but he furnished no information. . . and was never an informant of the Bureau." Chief Council of the House Select Committee on Assassinations (the 1970s version of the Warren Commission), Robert Blakey, later suggested that Ruby was ingratiating himself with the FBI so he could buy leverage if picked up for gunrunning. If true, some of the leverage he hoped to gain may have been related to his financial woes. Although his strip club was quite lucrative, Ruby was in trouble for not paying his taxes. By the time he shot Oswald, he owed the IRS nearly $40,000. This was at a time when a family earning $7,500 a year was doing well.

The most likely scenario is that Jack Ruby was under orders to kill lee Oswald. His Cuban and crime contacts prior to 1963, along with eyewitness reports connecting him with conspirators David Ferrie and Frank Sturgis certainly put Ruby in the right company for being so involved. And his behavior during and after the homicide of John Kennedy lends credence to the idea that Jack Ruby eliminated Lee Oswald to prevent Oswald from betraying the plot to kill the President. Indeed, once the Dallas police had apprehended Oswald, Jack Ruby took a manifest interest in the accused assassin. Bearing in mind that Kennedy was shot at 12:30pm, consider Ruby's movements during the forty-eight hours following that murder.

Ruby at Henry Wade's Press Conference announcing capture of Oswald |

Oswald was arrested in the Texas Theatre after a man one officer said "looked one hell of a lot" like Jack Ruby told the police what row the man they were looking for was sitting in. This occurred at 1:27pm. At 2:00pm, Ruby was seen leaving Parkland Hospital where the President had been pronounced dead. From 4:00pm until just past 7:00pm, he was at the Dallas Police Headquarters. By 9:00pm that evening he was at his own apartment where he made several telephone calls. He left in time to visit a local synagogue by 10:00pm. Ruby returned to the Dallas PD by 11:00pm, where he brought sandwiches to the officers and killed time awaiting the press conference just after midnight, November 23. the stars of the conference were District Attorney Henry Wade (of the future Supreme Court decision Roe v Wade) and Lee Harvey Oswald. Wade made a reference to a political organization to which Oswald had belonged and from a table in the back of the room, Ruby corrected the error. "Henry, that's the Fair play for Cuba Committee!" At the time no one thought to ask how a local strip club owner would be aware of the correct name of a political group that had as its one and only local member the recently accused murderer of the President.

Less than one hour later, Ruby was buying food and drink for the news staff of KLIF Radio. By 2:00am he was back downtown talking about the previous day's big story with an employee and a friend on the police force. Wrapping up discussions quickly, he delivered a racing form to a local newspaper, picked up his roommate, George Senator, and went back to the Carousel Club. A few minutes after 4:00am, Ruby took a camera and another employee out to the expressway and in an act of future irony, photographed a billboard that demanded the impeachment of Supreme Court Chief Justice Earl Warren. At 8:00am, Ruby returned to police headquarters and a few minutes later called a local radio station to ask what time Oswald would be transferred to the county jail.

Shortly after 2:30am, November 24, Ruby called Lieutenant Billy Grammer and told him to change the transfer plans for Oswald or "We're going to kill him right there in the basement." The pronoun choice demonstrates the actions of two or more people. The fact of the warning itself suggests that Ruby did not want to kill Oswald but could only get out of it due to circumstances beyond his control, such as a change of transfer plans.

At 11:17am, Ruby sent an employee named Karen Carlin $25 by Western Union from an office just down the street from the police department.

At 11:20am a car horn tooted and the jail elevator doors opened. Oswald, handcuffed to detective Jim Leavelle, was led out to be slaughtered. One reporter shouted, "Here he comes!" Another newsman moved in close and hollered "Do you have anything to say in your defense?" Oswald glanced at Ruby with a look of familiarity. Seconds later, Ruby bounded forward, shouted the last name of his victim, and rammed his .38 into Oswald's stomach, firing one shot. The bullet punctured the abdomen, pierced two arteries and ripped his spleen, pancreas, liver and right kidney. All this occurred as millions watched on television. Oswald was pronounced dead at 1:07pm.

The days later, Jack Ruby was indicted for first degree murder. On March 14, 1964, he was convicted and sentenced to death. The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals reversed the conviction in October 1966 and ordered a new trial. On December 9 Ruby was moved to parkland Hospital due to a persistent cough and nausea. he died of cancer January 3, 1967.

Researchers have been fascinated by Ruby's testimony to the Warren Commission. Oswald's killer begged for three hours to be taken out of jail and to go to Washington with the Chief Justice so he could testify safely and tell the Commission what he knew about the assassination. earl Warren refused. Exasperated, Ruby declared, "Well, you won't ever see me again. A whole new form of government is going to take over the country and I know I won't live to see you another time." When the Warren report was issued, it asserted that John Kennedy had been killed by Oswald, who had acted alone. According to polls, the majority of Americans have never believed this.

"No, Sir. I'm just a patsy." |

The literal visualization of Oswald's murder--within the context of subsequent events--has had the serendipitous effect of desensitizing Americans to the motivations and consequences of just such violent acts. When reports surfaced in September 1997 that photographers who may have contributed to the fatal car accident that killed Princess Diana and two others crawled onto the car's windshield to photograph the death in process, the public may have been horrified but certainly was not surprised. Cynicism about such monstrous acts is subtle, real and widespread in our culture. The filmed slaying of Lee Harvey Oswald served to condition the public against a need for resolution. A "we'll never know what really happened" attitude became pervasive and was applied to such societal cataclysms as the Vietnam War, Watergate, The October Surprise, Iran-Contra, the Impeachment of Bill Clinton, and the Presidential Election of 2,000. The accused assassin did not stand trial. Ruby died before his retrial. And by 1970, most of the people who could have illuminated crucial details had ceased to exist. And there were very few Howard Beale types urging people to shout.

b.jpg)

The_American_President_Movie_1.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment